Inverted Index Performance and Merkle Tree Syncronization

Napkin friends, from near and far, it’s time for another napkin problem!

As always, consult sirupsen/napkin-math to solve today’s problem, which has all the resources you need. Keep in mind that with napkin problems you always have to make your own assumptions about the shape of the problem.

We hit an exciting milestone since last with a total of 500 subscribers! Share the newsletter (https://sirupsen.com/napkin/) with your friends and co-workers if you find it useful.

Solving problem 8 is probably the most comprehensive yet… it took me 5 hours today to prepare this newsletter with an answer I felt was satisfactory enough, I hope you enjoy!

I’m noticing that the napkin math newsletter has evolved from fairly simple problems, to serving simple models of how various data structures and algorithms work, then doing napkin math with these assumptions. The complexity has gone way up, but I hope, in turn, so has your interest.

Let me know how you feel about this evolution by replying. I’m also curious about how many of you simply read through it, but don’t necessarily attempt to solve the problems. That’s completely OK, but if 90% of readers read it that way, I would consider reframing the newsletter to include the problem and answer in each edition, rather than the current format.

Problem 9

You may already be familiar with the inverted index. A ‘normal’ index maps e.g. a primary key to a record, to answer queries efficiently like:

SELECT * FROM products WHERE id = 611

An inverted index maps “terms” to ids. To illustrate in SQL, it may efficiently help answer queries such as:

SELECT id FROM products WHERE title LIKE "%sock%"

In the SQL-databases I’m familiar with this wouldn’t be the actual syntax, it varies greatly. A database like ElasticSearch, which is using the inverted index as its primary data-structure, uses JSON and not SQL.

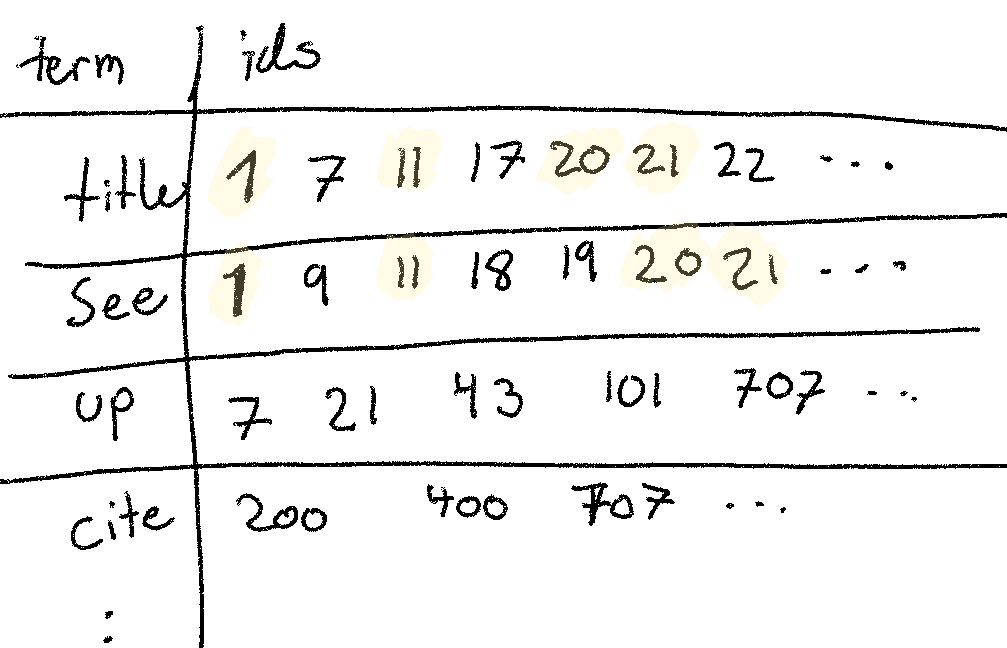

The inverted index might look something like this:

If we wanted to answer a query to find all documents that include both the words

title and see, query='title AND see', we’d need to do an intersection of

the two sets of ids (as illustrated in the drawing).

(A) How long do you estimate it’d take to get the ids for title AND see

with 2 million ids for title, and 1 million for see?

(B) What about title OR see?

(C) How do the Lucene nightly benchmarks compare for (A) and (B)? This file shows some of the actual terms used. If they don’t line up, how might you explain the discrepency?

(D) Let’s imagine that we want title AND see and order the results by the

last modification date of each document. How long would you expect that to take?

Answer is available in the next edition.

Answer to Problem 8

Last month we looked at a syncing problem.. What follows is the most deliberate answer in this newsletter’s short history. It’s a fascinating problem, I hope you find it as interesting as I did.

The problem comes down to this: How does a client and server know if they have the same data? We framed this as a hashing problem. The client and server would each have a hash, if they match, they have the same data. If not, they need to sync the documents!

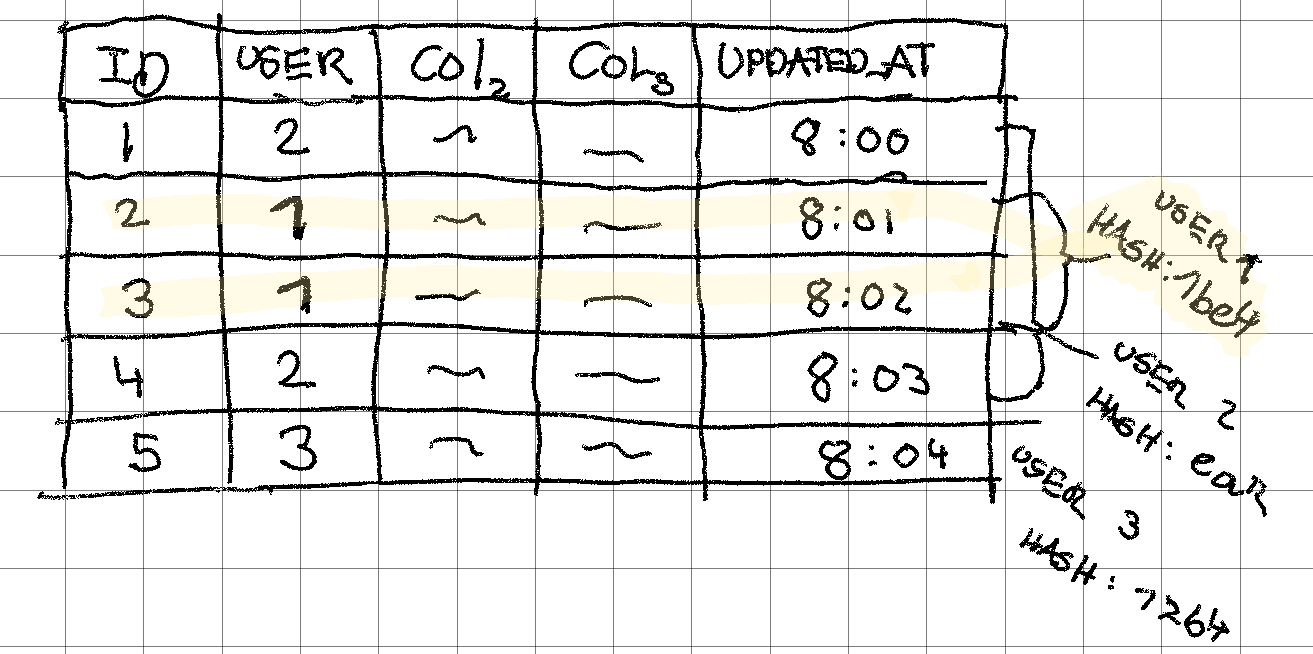

The query for the client and server might look something like this:

SELECT SHA1(*) FROM table WHERE user_id = 1

For 100,000 records, that’ll in reality return us 100,000 hashes. But, let’s assume that the hashing function is an aggregate function without confusing with very specific syntax (you can see who to actually do it here.

(a) How much time would you expect the server-side query to take for 100,000 records that the client might have synced? Will it have different performance than the client-side query?

We’ll assume each row is about 256 bytes on average (2^8), which means we’ll

be reading ~25Mb of data, and subsequently hash it.

Now, will we be reading this from disk or memory? Most databases maintain a cache of the most frequently read data in memory, but we’ll assume the worst case here of reading everything from disk.

We know from the reference that we can hash a mb in roughly 500 us. The

astute reader might notice that only non-crypto safe hashing are that fast (e.g.

CRC32 or SIPHASH), but SHA1 is in a crypto-family (although it’s not

considered safe anymore for that purpose, it’s used for integrity in e.g.

Git and many other systems). We’re going to assume we can find a non-crypto hash

that’s fast enough with rare collissions. Worst case, you’d sync on your next

change (or force it in the UI).

We can also see that we can read 1 mb sequentially at roughly 200 us/mb, and

randomly at roughly 10 ms/mb. In Napkin Problem 5 we learned that reads

on a multi-tenant database without a composite primary key that includes the

user_id start to look more random than not. We’ll average it out a little,

assume some pre-fetching, some sequential reads, and call it 1 ms/mb.

With the caching and disk reads, we’ve got ourselves an approximation of the

query time of the full-table scan: 25 Mb * (500 us/Mb + 1 ms/Mb) ~= 40ms.

That’s not terrible, for something that likely wouldn’t happen too often. If

this all came from memory, we can assume hashing speed only to get a lower bound

and get ~12.5ms. Not amazing, not terrible. For perspective, that might yield

us 1s / 10ms = 100 syncs per second (in reality, we could likely get more by

assuming multiple cores).

Is 100 syncs per second good? If you’ve got 1000 users and they each sync once

an hour, you’re more than covered here (1000/3600 ~= 0.3 syncs per second).

You’d need in the 100,000s of users before this operation would become

problematic.

The second part of the questions asks whether the client would have different performance. The client might be a mobile client, which could easily be much slower than the server. This is where this solution starts to break down for so many documents to sync. We don’t have napkin numbers for mobile devices (if you’ve got access to a mobile CPU you can run the napkin math script on, I’d love to see it), but it wouldn’t be crazy to assume it to be an order of magnitude slower (and terrible on the battery).

(b) Can you think of a way to speed up this query?

There’s iterative improvements that can be done on the current design. We could

hash the updated_at and store it as a column in the database. We could go a

step further and create an index on (user_id, hash) or (user_id, updated_at). This would allow us much more efficient access to that column!

This would easily mean we’d only have to read 8-12 bytes of data per record,

rather than the previous 256 bytes.

Something else entirely we could do is add a WHERE updated_at .. with a

generous window on either side, only considering those records for sync. This is

do-able, but not very robust. Clocks are out of sync, someone could be offline

for weeks/months, … we have a lot of edge-cases to consider.

Merkle Tree Synchronization

The flaw with our current design is that we still have to iterate through the 100,000 records each time we want to know if a client can sync. Another flaw is that our current query only gives us a binary answer: the 100,000 records are synced, or the 100,000 records are not synced.

This query’s answer then leaves us in an uncomfortable situation… should the

client now receive 100,000 records and figure out which ones are out-of-date? Or

let the server do it? This would mean sending those 25 Mb of data back and forth

on each sync! We’re starting to get into question (C), but let’s explore

this… we might be able to get two birds with one stone here.

What if we could design a data-structure that we maintain at write-time that would allow us to elegantly answer the question of whether we’re in sync with the server? Even better, what if this data-structure would tell us which rows need to be re-synced, so we don’t have to send 100,000 records back and forth?

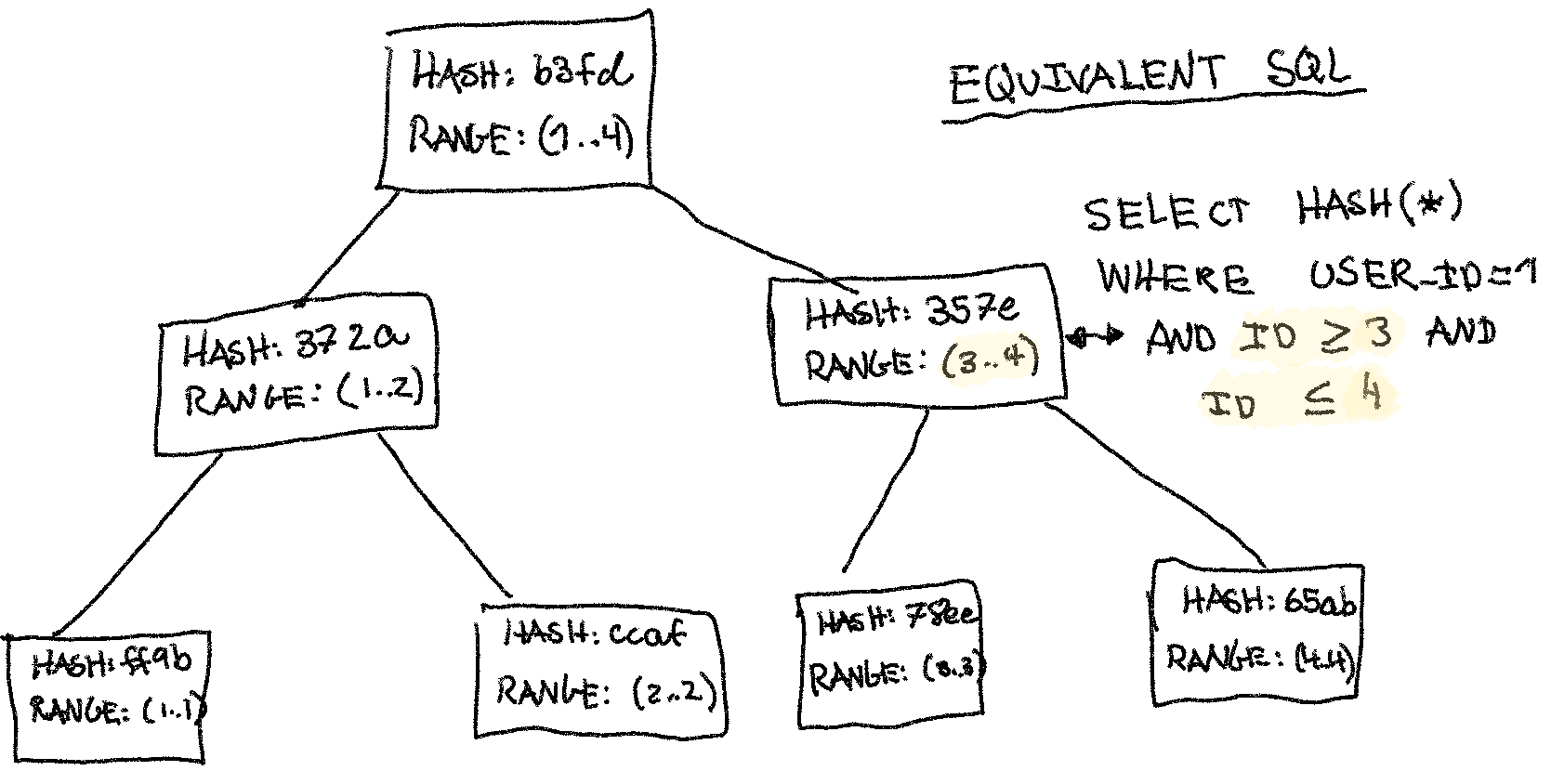

Let’s consider a Merkle tree (or ‘hash tree’). It’s a simple tree data structure where the leaf nodes store the hash of individual records. The parent stores the hash of all its children, until finally the root’s hash is an identity of the entire state the Merkle tree represents. In other words, the root’s hash is the answer to the query we discussed above.

The best way to understand a Merkle tree is to study the drawing below a little:

In the drawing I show a MySQL query to generate an equivalent node. It’s likely not how we’d generate the data-structure in production, but it illustrates its naive MySQL equivlalent. The data-structure would be able to answer such a query rapidly, wheras MySQL would need to look at each record.

If we scale this up to 100,000 records, we can interpolate how the root would store

(hash, (1..100,000)), its left child would store (hash, (1..50,000)), and

right child would store (hash, (50,001..100,000)), and so on. In that case, to

generate the root’s right node the query in the drawing would look at 50,000

records, too slow!

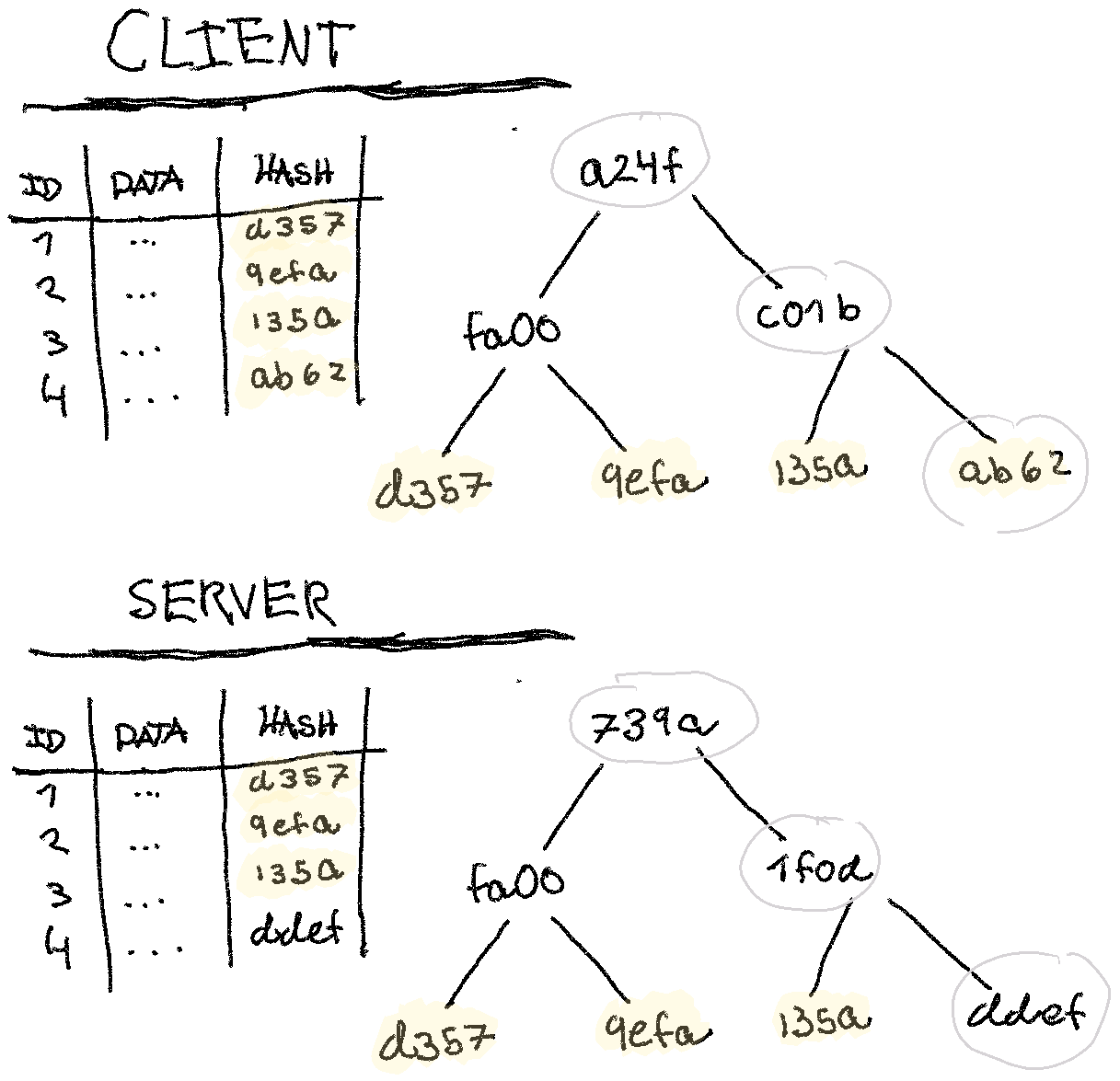

Let’s assume that the client and the server both have been able to generate this data-structure somehow. How would they efficiently sync? Let’s draw up a merkle tree and data table where one row is different on the server (we’ll make it slightly less verbose than the last):

Notice how the parents all change when a single record changes. If the server

and client only exchange their merkle trees, they’d be able to do a simple walk

of the trees and find out that it’s indeed id=4 that’s different, and only

sync that row. Of course, in this example with only four records, simply syncing

all the rows would work.

But once again, let’s scale it up. If we scale this simple model up to 100,000

rows, we’d need to still exchange 100,000 nodes from the Merkle tree! It’s

slightly less data, since it’s just hashes. Naively, the tree would be ~2^18

elements of perhaps 64 bits each, so ~2mb total. An order of magnitude better,

but still a lot of data to sync, especially from a mobile client. Notice here

how we keep justifying each level of complexity by doing quick calculations at

each step to know if we need to optimize further.

Let’s try to work backwards instead… Let’s say our Merkle tree has a maximum

depth of 8.. that’s 2^8 = 256 leaf nodes (this is what Cassandra does to

verify integrity between replicas). This means that each leaf would hold

100,000 / 256 = 390 records. To store a tree of depth 8, we’d need 2^(8+1) = 2^9 = 512 nodes in a vector/array. Carrying our 64-bit per element assumption

from before to store the hash, that’s a mere 4kb for the entire Merkle tree. Now

to syncronize, we only need to send or receive 4kb!

Now we’ve arrived at a fast Merkle-tree based syncing algorithm:

- Client decides to sync

- Server sends client its 4kb Merkle tree (fast even on 3G, 10-100ms including round-trip and server-side processing overhead)

- Client walks its own and the server’s Merkle tree to detect differences

(operating on

2 * 4kbtrees, both fit in L1 CPU caches, nanoseconds to microseconds). - Client identifies the leaf nodes which don’t match (

log(n), super fast since were traversing trees in L1). - Client requests the ids of all those leaf nodes from the server (

390 * 256 bytes = 100Kbper mismatch)

To actually implement this, we’d need to solve a few production problems. How do

we maintain the Merkle tree on both the client and server-side? It’s paramount

its completely in sync with the table that stores the actual data! If our table

is the orders table, we could imagine maintaining an orders_merkle_tree

table along-side it. We could do this within the transaction in the application,

we could do it with triggers in the writer (or in the read-replicas), build it

based on the replication stream, patch MySQL to maintain this (or base it on the

existing InnoDB checksumming on each leaf), or something else entirely…

Our design has other challenges that’d need to be ironed out, for example, our

current design assumes an auto_increment per user, which is not something most

databases are designed to do. We could solve this by hashing the primary key

into 2^8 buckets and store these in the leaf nodes.

This answer to (B) also addresses (C): This is a stretch question, but it’s

fun to think about the full syncing scenario. How would you figure out which

rows haven’t synced?

As mentioned in the previous letter, I would encourage you to watch this video if this topic is interesting to you. The Prolly Tree is an interesting data-structure for this type of work (combining B-trees and Merkle Trees). Git is based on Merkle trees, I recommend this book which explains how Git works by re-implementing Git in Ruby.