How I Read

March 2020: Dan Shipper wrote an awfully nice post about a more recent iteration of this system.

Until a few years ago, I didn’t spend much time reading. Today, I spend a few hours every week reading, amounting to somewhere between 30 and 50 books a year. My reading habit has evolved significantly over the past couple of years and surely will continue to. In this post, I will describe how I approach my reading. You may think it’s elaborate (other people’s reading systems rub me the same way), however, keep in mind it’s evolved slowly over the years.

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system. – John Gall

It’s also worth noting that this is not an aspirational post. This is what I actually do, and have done for a while—otherwise, I wouldn’t think it would be worth sharing. I often think of the classic Charlie Munger quote on reading, he’s not wrong:

In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time — none, zero. You’d be amazed at how much Warren reads—and at how much I read. My children laugh at me. They think I’m a book with a couple of legs sticking out. – Charlie Munger

The post is divided into a section for each part of the reading process: (1: Sourcing), (2: Choosing), (3: Reading), and (4: Processing).

Sourcing

Whenever I stumble upon a recommendation for a book, I will follow the link to Amazon and send the page to Instapaper. I have a script that automatically converts any Instapaper book links into rows in an Airtable. Endorsements from trusted sources will be added, too. This script will automatically add metadata about the book from Goodreads such as genre, year published, author, and so on.

What would I like to improve about choosing?

Whenever I send the book to Instapaper, I’d like to attach a name to it and automatically add them as an endorser. There are also certain people whose book recommendations I seek. Automatically adding their endorsed books to my feed would be valuable. If I start going deep on a topic, I may want to read a follow-up book on the topic and will go through my sourcing list first. Attaching a summary or similar would help make the searches more fruitful. In general, I would like someone else to solve this problem for me. Improving it further to aid in choosing more would be a non-trivial amount of engineering—see next section. See the next section, (2: Choosing), for a much more elaborate answer to how I’d like to improve the sourcing and choosing process altogether.

What are changes I’ve made in sourcing?

I used to have a habit of buying the books I wanted to read instead of simply sourcing them. That’s an expensive sourcing method. Inevitably, it grew into a large number of unread books on my Kindle, which made me often dread opening it. It felt like an ever-growing to-do list (where each item takes many hours to complete). This is popularized as an anti-library—I don’t think this translates to the Kindle world well, but may work for the physical realm for books you know you want to read. Most importantly, it means that finishing a book always becomes a new adventure in choosing a new book without considering the sunk cost of already having bought another book which may mean I read less relevant books. Generally, I subscribe to not counting money spent on books. It’s $10, and it could very easily change your life. That’s a bargain. I will acknowledge this is a privileged argument, but libraries make good allies if buying is too expensive. Old books (which have stood the test of time, see next section) often cost pennies on Amazon.

Choosing

For choosing books, I have a couple of heuristics I apply as I scurry through my sourcing list, Google, Goodreads, and other trusted sources:

1. What book is most applicable right now? If I can find a book that I can start applying right now in whatever I’m dealing with, it’ll take precedence over any other heuristic. If I’m about to recruit, reading books about building teams and recruiting would be highly applicable. With an immediate opportunity to put it into practice, it is much easier to have things stick and make an impact. This is the most important heuristic, however, it is often challenging to find such a book. Especially with the relatively poor sourcing tools I feel that I have available.

2. Syntopical reading. If I’ve been diving into a single topic, I may try to pick up a few more works in the same category to make sure I see the problem from different angles. I find that this helps strengthen the concepts too, as I get to run an internal mock dialog between the authors of the books where they agree or disagree. If it’s on a topic that strongly satisfies (1), I am more likely than not to do syntopical reading. On the other hand, if I am mostly looking for an overview of a topic—I may save syntopical reading for the future.

3. Books that have aged well. If the book has been out 10 years, it’s likely it might still be relevant another 10 years from now. If it’s been out for 100 years, it’s likely it’ll be around for another 100 years. If I am diving into recruiting due to heuristic (1), I’ll look for the book that’s 10 years old, not the one that was published this spring. In fast-moving fields, newer can be better, in which case I may start with new, and then read the old. This applies to e.g. software, where I’ll likely default to what was published recently but often go back and understand how we ended up here by reading older material. In most sciences, old is good. I found Darwin’s original work surprisingly readable.

4. What discipline or topic am I weak in? I believe that at some point, optimizing for breadth in your reading to complement your depth becomes more impactful than going even deeper. As Munger puts it, accumulate the big ideas from the big disciplines. There are so many disciplines where people learn to think in different ways to solve different problems. Over time, I’d like to get a rudimentary understanding of most of the major disciplines: law, biology, economics, history, physics, and the list goes on. This will take a lifetime, but I think the process will be both enjoyable and useful. I attempt to balance disciplines, but this easily gets thrown off by other heuristics. There’s a fine balance with (1). Breadth, (4), is most useful with depth, (1).

5. Modern translations or interpretations are not inherently bad, especially as introductions to a topic. Old is good, but can be taken too far. I enjoyed reading A Guide to the Good Life from 2008 as an introduction to stoicism much more than Letters from a Stoic from BC something something. Here, the concepts applied (Stoicism) have stood the test of time—but it may be easier to apply if written by someone in the 21st century. If you’re really into it, by all means, go to the primary source (I did). Similarly, wanting to take advantage of knowing Danish I started reading Kirkegaard a few years ago. I preferred the English translation because you won’t get chastised for modernizing a translation the same way you would for modernizing the origin language. If you’re really into a topic, it’s silly to not go to the primary source a book or two into the topic, though. If you’re into stoicism (as pointed out here), go to the original works. They’re very readable, otherwise, the ideas would not have aged as well as they did.

6. What are my friends reading? If my friends have read a book, that’s a free opportunity to talk with them about it or ask them whether it fits my criteria. It’s a free book club opportunity, helping to nudge the concepts into long-term memory and get perspective. I don’t want to have 100% overlap with my friends, but once in a while, if the stars align—I like this opportunity. In general, I abuse friend’s reading more to assist with (1: Applicability), as these can be difficult books to find.

7. Audiobooks for narrative, Kindle for anything else. While less of a heuristic for choosing the next book, this is still something that I find useful. If a book has a narrative, such as history, biographies, or novels—then it falls in the Audiobook bucket for me. I may experiment with re-reads as audio at some point. For anything else, I’ll read it on my Kindle. Some narratives are too technical for Audiobooks to me, for example, I started listening to a book about the fall of Enron—too difficult to follow through audio due to a large amount of industry and finance jargon.

8. Skim the free sample of your top x books. I learned from Dan Doyon

that Amazon will send you free samples of books. His Kindle is ladled with

Kindle samples, and he’ll choose his next book by skimming through 10s of these

to hit one he finds most interesting at that moment. I’ve started adopting

skimming the top samples that come out of the other heuristics. I find this a

useful supporting heuristic for e.g. (1: Applicability) and (4: Breadth). It’s

easy to choose a book especially on a new topic where the idea of knowing

about it (e.g. basic accounting) sounds intriguing, but you may just not be in

the right place and time that it’s interesting enough for you to follow through.

What would I like to improve about choosing?

What bothers me most about my choosing and sourcing is that it’s at the wrong abstraction level. I should be choosing topics and skills and sorting those by the applicability heuristic, rather than books. While books are useful, the ultimate goal here is not to read books—but to learn. There are other ways to learn than books: courses, classes, conversations, exercises, travel, coding ideas, crafts, and so on. “Reading” as a way to acquire knowledge is useful, and I see the majority of my time being spent here for personal development—however, I would like to not choose the next book but the next topic. Not: “This book about photography” but rather “The topic of photography” with the supporting sourcing and choosing tooling that’ll allow me to then dig into books.

The tooling I have now does not support my (1: Applicability) and (4: Breadth) heuristics well. Self-assessing which skills I’m weak assumes I have no blind spots, which would be incredibly naïve to believe. (6: Friends) and what they read help shed some light on those blind spots, but are largely disconnected from what might be useful for me. I am not sure exactly what I want, but I feel that I should move towards a list of topics I would like to get into and sort them by attributes such as current knowledge about the topic, upper-bound return on investment, lower-bound return on investment, applicability, enjoyment, and perhaps a couple others. This would allow me to go much wider, from playing chess (which I likely don’t have a single book in my sourcing list about) to a rudimentary understanding of a new language (no Spanish grammar books in my sourcing list, I am afraid), because it would gain me the ability to visualize my opportunity cost more clearly and put myself another level away from the currently fairly subjective choice of next book. I would certainly not challenge that there can be a serendipitous highly positive benefit to at times choosing semi-random, recommended books in a broad topic such as management. I feel that’s what I end up doing most of the time, and I crave more.

I crave too much structure, but I feel that significant investment into this aspect would pay serious dividends. It’s likely that I will experiment with an Airtable for this over the coming years and make changes to this article. Most of all I hope someone else will build this, but most likely it’s far too systematic. It is also possible that chaos here is possible, but I refuse to believe I cannot get a system that outperforms chaos by at least 10-20%—which would be a major win over a lifetime.

What are changes I’ve made in choosing?

This used to be “go down the list on Audible” or “go down the list on the Kindle” of books already purchased. However, “just in time” choosing has been much more effective to satisfy the most important heuristic (1): What book can have the biggest impact for me right now? In general, I would advise looking at your choosing akin to an efficient factory. You shouldn’t have massive piles of inventory in front of every machine, but rather optimize the overall throughput through the factory.

Reading

Typically, I have about 3 books on the go: An Audiobook, a fiction book on the Kindle, and a non-fiction work on the Kindle. When reading, I attempt to focus on a couple of things. The majority of them to improve retention.

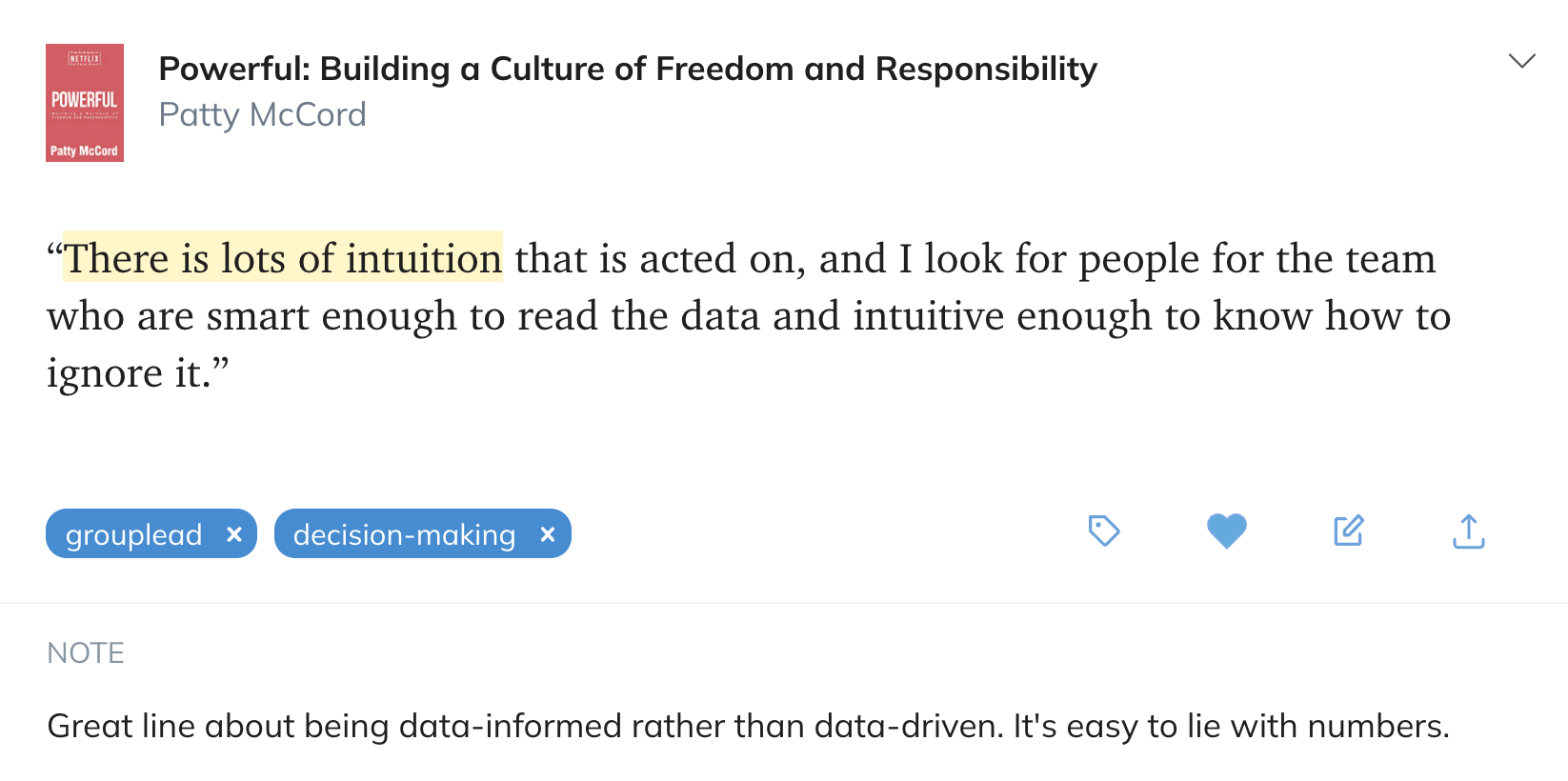

1. Highlights. I will highlight the interesting parts of a book. Often, I take notes too as I have too many times been in the situation where returning to the highlight I have a hard time figuring out why I found it important at the time of reading. Typing on the Kindle is painful to begin with, but you get the hang of it eventually. I use Readwise for working with my highlights (more on this in the processing stage), and use tags, special tags to combine highlights on the fly, and their header tags to add sections for a table of contents. I also highlight words I don’t know (or don’t use), to later process them into my vocabulary.

2. Skimming and skipping. I make fairly liberal use of skimming and skipping, especially in non-fiction where not every chapter will have an equivalent impact for me. Skimming the first and last few pages of a chapter often gives you a great idea about whether the chapter is worth reading for you. For example, years ago I went to Brazil, and before going I wanted to read a short book about the history and culture of the country. There were 3 chapters about sports in Brazil, something I wasn’t interested in. I got the gist of it from the first and last few pages and simply skipped. When I read Principles, I skipped the biography and went straight to the principles, deciding I’d read the biography chapter later if the principles were interesting enough. It felt oddly liberating when I realized there’s no book police that’ll come knocking on your door when you skip a chapter.

3. Visualizing. Ever since reading Moonwalking with Einstein I’ve incorporated memory palaces into more aspects of my life. I’ve experimented with summarizing a book as I go in a memory palace, and this worked out quite well. It generally meant that it was easier for me to remember the book in general. Memory palaces aren’t just about being able to memorize a list, but also a concrete way to connect key points into your wetware. What I found surprising was that when something would remind me of the points from a book I’ve built a palace for for, I’m thrown right into the memory edifice to connect it. While in the palace, I find that I will often spend time going backwards and forwards and re-iterate the other concepts—a form of spaced repetition. There’s still more to explore here, but there’s certainly something to it. Think of it like when you read a novel, you’re always visualizing what’s going on. The more effort you put into this, the easier the novel is to remember. The longer you put an effort in, the easier it gets to create more and more elaborate images over time. I haven’t been as diligent with this practise for the past few books, but I plan to continue to experiment with it.

4. Metaphors and relations. This relates back to visualization; anything you

can do to make a book more vivid helps. If you can relate concepts from the book

to something else, it does wonders. A while ago, it felt overdue to gain a

technical understanding of how simple Blockchains work. A friend asked me to

explain it to him, and we constantly related each concept back to concepts and

metaphors we already understood. In about an hour he gained a deep enough

understanding that he could go explain it to someone else, in quite elaborate

technical detail. I attribute that to relating everything to a real-life

metaphor, e.g. ‘hashing’ in cryptography was conceptualized as akin to a fire

turning into ash; impossible to reverse, and the slightest adjustment in initial

conditions would make the configuration of ashes different. One of the most

important relations I find is to attempt to see if the concept would’ve made a

scenario in your life play out differently, had you known it. I like to think of

each past event having n lessons you can extract out of it. It’s important to

not leave any lessons on the table, and to suck these experiences dry—you

need to revisit them for decades to come. It’s a bit like a machine learning

algorithm (it’s actually exactly like a machine learning algorithm, which of

course, is inspired by humans). You’re constantly adding to the algorithm with

new mental models and an enriched understanding of the world. When you’ve

changed the algorithm, you need to re-train it on your data-set consisting of

your collected experience.

5. Summarize every chapter in your head. I don’t remember where I read or heard this, but someone said that one of the best pieces of advice they’d ever gotten was that every time they’d leave a room, they should stop at the door and summarize to themselves what just happened. What did you just learn? What just happened in that meeting? What was on that person’s mind? When I finish a chapter in a book, I try to quickly summarize it in my head. If I’m building a palace for the book, I’ll attempt to make up an image and plant it. This is often surprisingly hard, but I’ve noticed improvements as a result. It’s like the end of a (good) meeting, where someone will summarize all the actions and outcomes. Ever been to one where that doesn’t happen? It can feel like a waste of time.

6. Re-read. The best books I will try to read again. I’ve done it so far for perhaps half a dozen books and it’s been rewarding every time. In general, I think we can treat the best books and articles more like music playlists. Reading them again and again, with sufficient repetition in between to make them relevant and fresh anew. For articles, I have a script that’ll feed them back to me on a spaced repetition schedule automatically in Instapaper. I wrote more about this here.

What would I like to improve about reading?

My retention here is still not quite as good as I would like, although I think a fair bit of that comes from the processing (next section). I would like to more diligently build palaces. I haven’t done it for the past 5-10 books I’ve read, but the ones I did I’ve found myself going back to more often than not. I don’t take as many notes to my highlights as I’d like to, I think more focus on these two will make the biggest difference currently because they’ll both benefit the processing stage.

I dream of the day where I can see the highlights of friends. This would be a fantastic opportunity to start interesting conversations with people and build a deeper understanding of the book while feeling much less forced than a book club.

What are changes I’ve made to reading?

My reading process has been fairly additive. I’ve mostly added more and more structure to the way I read, any more effort I can put in here to twist and turn the points made end up being better than not doing it. The fear here is doing too much. As mentioned in the processing stage, to simplify, I will need to figure out what works and what doesn’t.

Processing

Reading, to me, is worth the most if I can remember the ideas. I don’t think you will always be able to map an idea back to its source, meaning, just because you can’t summarize Thinking Fast and Slow eloquently, doesn’t mean it didn’t influence you.

Reading and experience train your model of the world. And even if you forget the experience or what you read, its effect on your model of the world persists. Your mind is like a compiled program you’ve lost the source of. It works, but you don’t know why. – Paul Graham

It’s a cliché to complain about the length of books: “This idea could be explained in five pages! Why would they write an entire book?” This statement bothers me to no end. If you possess the discipline it takes to incorporate an idea into your wet-ware from article-length with no fail—then you’ve got some discipline that you would not self-discount with a blanket statement like that. No-one I’ve talked to who reads 10s of books a year, and have done so for years, would dream of saying this. They understand that reading is not just about passing words through your head.

Then why are books long? I’ll gently navigate around the “publisher’s require it to be 200+ pages” conspiracy, and instead focus on two points. First, it’s a form of spaced repetition. This wonderful, proven technique that can be applied to almost every corner of your life. It turns out, if a book is 200 pages, it’s going to take you a few spaced repetition cycles to read it, which raises the probability it’ll stick for you. Unless you are diligent about repetition, my pet theory is that most things that stick are somewhat random. You hear something today, and then in the next spaced repetition window a few days from now; you hear about it again. Then a week or so after that. If you consider how many new things we hear every day, I don’t think this is so crazy. Especially given how hyper-aware our brain is for these things, it wants to recognize them. I’ve noticed this is how most new English words transition from a spreadsheet to my real, active vocabulary. There’s a hint of random in there.

The second reason books are long, is that different ways of explaining an idea resonate with different people. For you, it may be that antifragility is best explained through a fitness analogy; you break down muscle, build them back up, ta-daa you are now stronger. For the foodie who makes an annual pilgrimage to New York, antifragility may draw the most connections (and thus stick best) when applied to why the ramen seems better every time you go back. Remembering an idea is some combination of the number of connections you can draw and spaced repetition. Anecdotally, I’ve observed that I remember new information in the space of software well. I can usually connect it to half a dozen things fairly quickly, which makes it hard to forget. If you tell me something I don’t know about the state of Crude Oil, I have little to connect it with and most likely I will not remember it tomorrow unless I put in more effort; spaced repetition, or ask enough questions that that half a dozen connections start appearing. But that’s work.

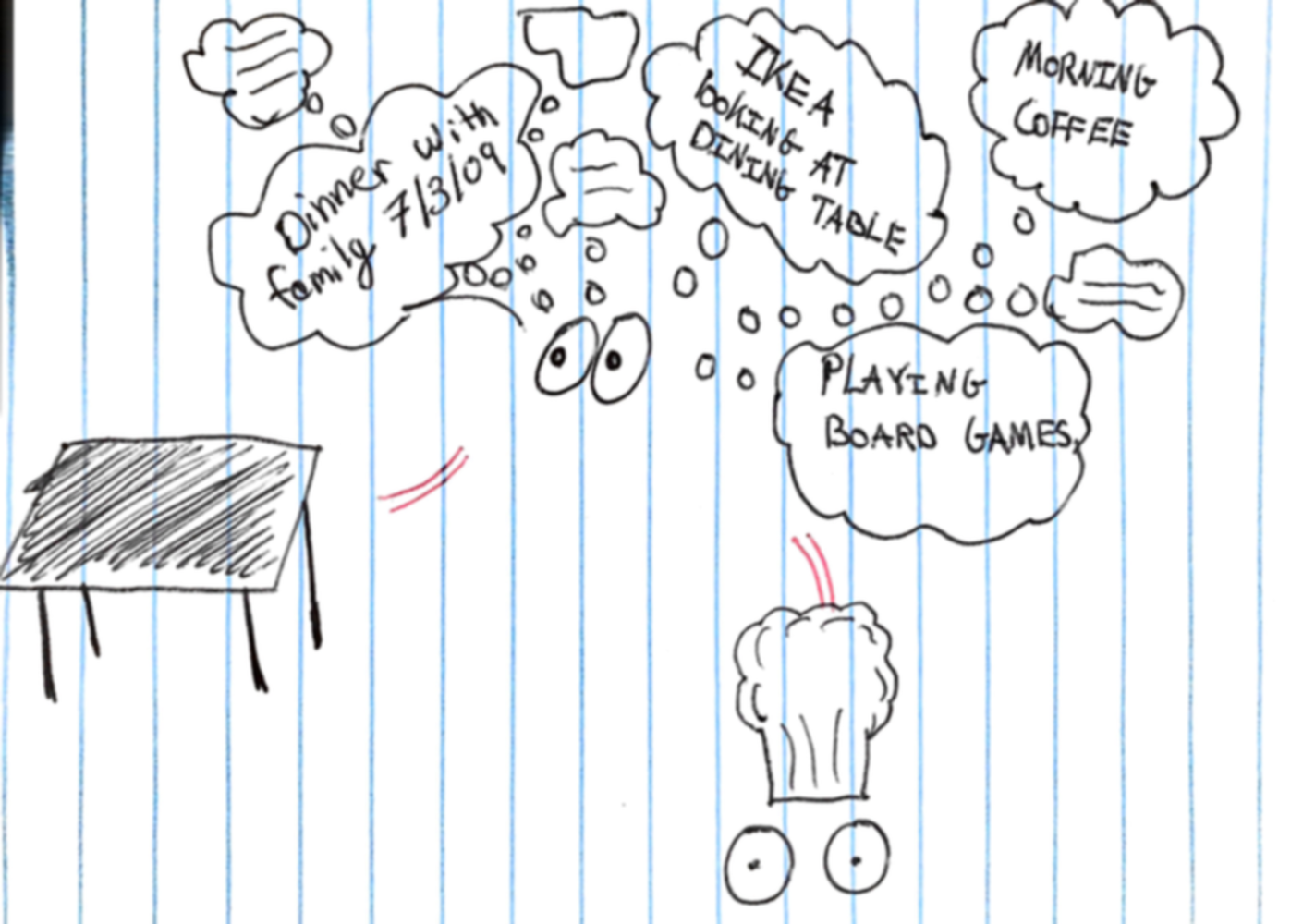

Turns out forming new memories needs to be hard. Otherwise, how is your brain to know what to remember and what not to? Imagine if every time you looked at a dining table, every single memory ever that had to do with a table was readily available. That’d be pretty uncomfortable. (The eyes with the cupcake on top below is my poor imitation of the exploding head emoji: 🤯)

Here are some of the steps I do after having read a book that I’ve done for a while.

1. Writing a review/summary. A few weeks after reading a book, typically I’ll write a short summary and review and publish it on Goodreads (example). This forces me to extract the key lessons from the book. Typically, I’ll use my highlights from Readwise.io to assist in extracting the key lessons from the book and throw them into the summary. You can see all my reviews on my Goodreads profile.

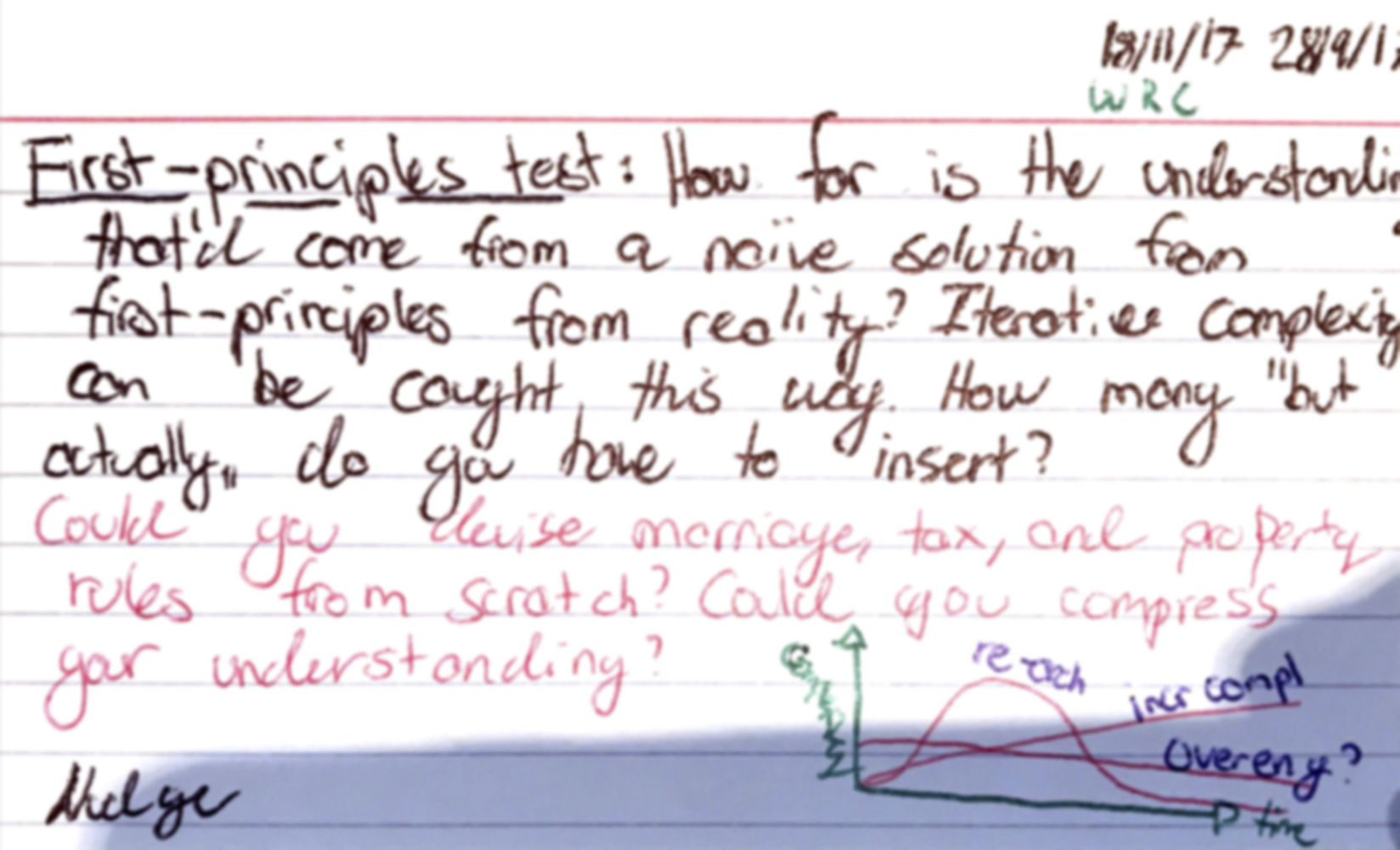

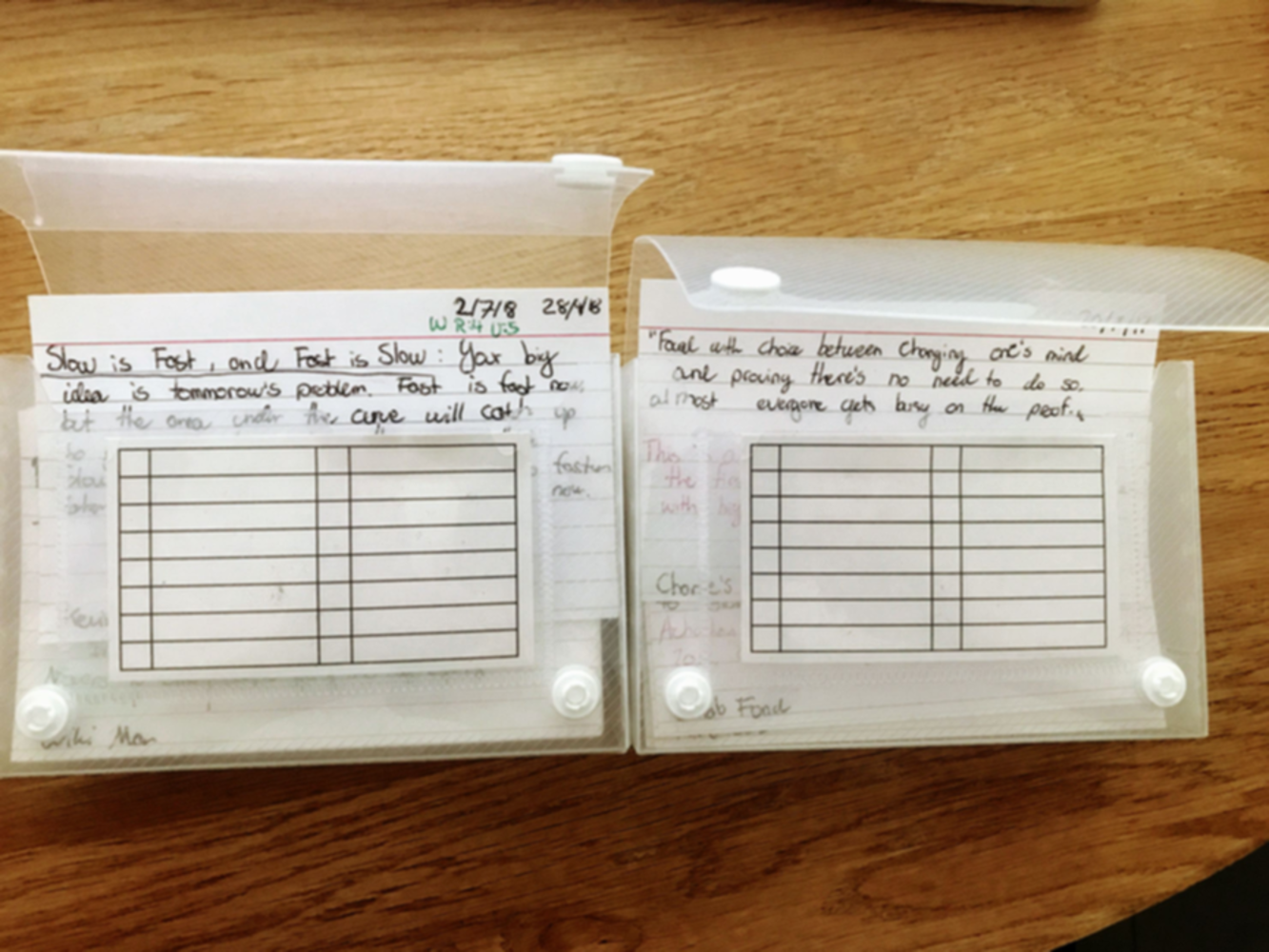

2. Converting highlights to index cards. Either at the same time as doing the review/summary or later, I will go through my highlights and find the ones I like most. Often, I end up spending hours (typically on a Saturday or Sunday morning) going into rabbit holes as part of polishing my highlights. This is fine, if they’re interesting, it helps me to build connections and stick them in long-term memory. For the best points in the books, often a combination of highlights and themes, I’ll create a physical index card. I try as much as possible to draw on the card and think of references to other books.

3. Reviewing index cards. I have two containers for my index cards. One with

index cards that have been processed at least once (left) and one for cards that

have yet to be processed (right). As you can see, the top card in the left box

is the one that was most recently reviewed (2nd of July, 2018) and the card on

top of the right box hasn’t been reviewed yet (only one date). As you see on the

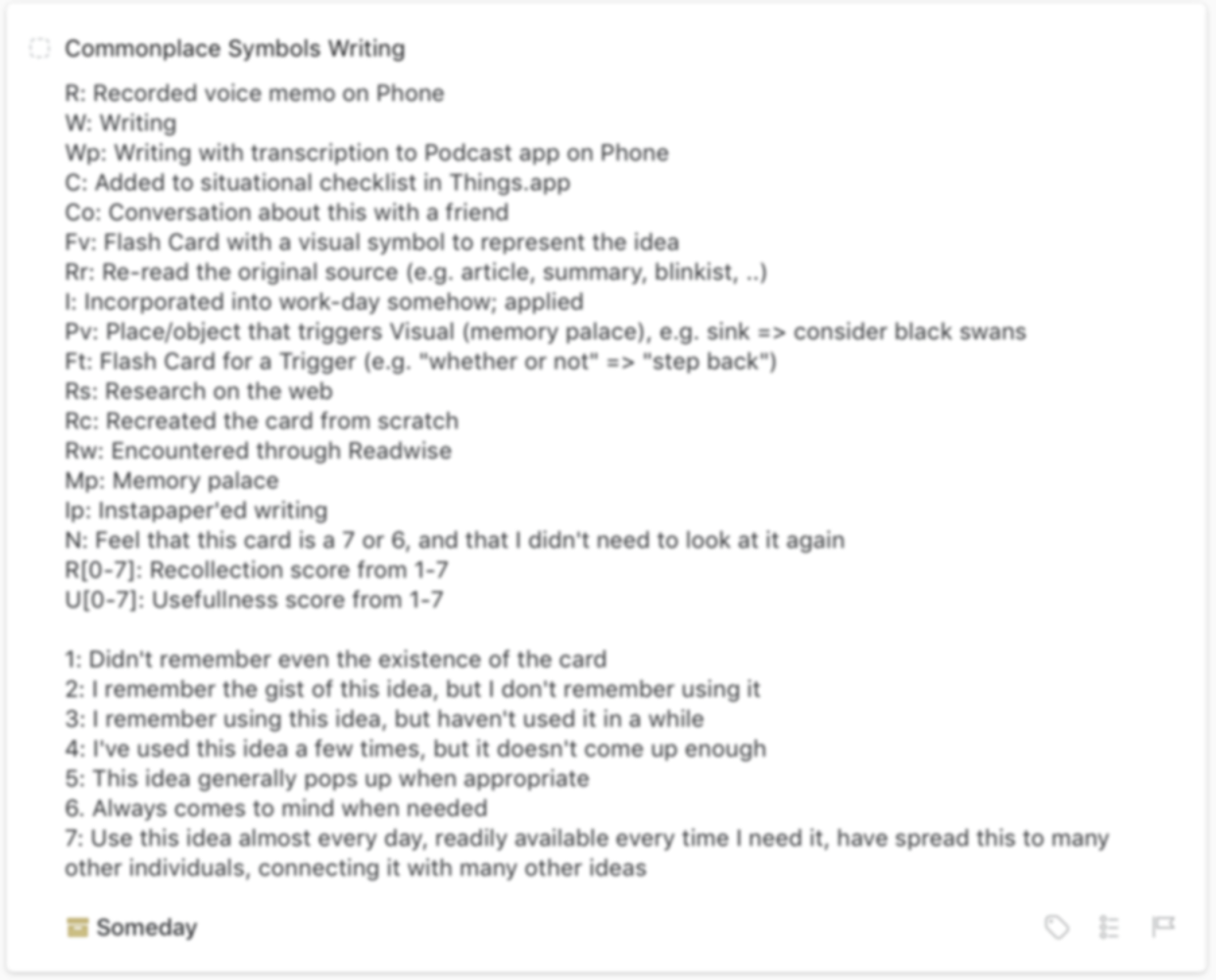

card above, and the card below, there are little symbols under the date. These

symbols have special meanings for what I did with the card at the same time. I

have a dozen or so symbols to experiment with what works best for retention over

time. W below means that I wrote at least 200 words about the content of the

card, attempting to draw new connections and elaborate on the idea. R is

followed by a number and rates how much I’ve applied this idea since last time.

U followed by a number is how useful this idea is, on a scale from 1 to 7.

These numbers are long-term to inform a better sorting algorithm if there are two

cards I can review now, I’d prefer the one with a low R value (not applied

yet), high U value (very useful), and where a long time has passed since last

reviewed. I may digitize this at some point (I’m terrified of losing these

cards), but this has worked well so far. Again, as with (2: Choosing), I think I

can beat randomness and sorting by date by at least 10%, which is a significant

improvement over the long-term. However, I’ll need some data first. Below, you

can see a full list of my symbols. Some are not deprecated, but many I continue

to use.

When I travel, I usually bring the box of unprocessed cards with me and spend some time reflecting on those cards. Some call this a “Commonplace Book”; i.e. a book with all the best snippets from everywhere. Why index cards and not a notebook? Well, notebooks can only grow so much in size, and are hard to change without becoming messy. Often, I’ll tear cards apart on a second review and re-write them for more clarity and backfill the dates. I can sort them however I want, which is difficult. Airtable would be a fantastic candidate for the Commonplace book but the physical aspect currently intrigues me.

If you’re after something similar, Readwise has a great feature to send you some of your highlights every day. Takes minutes to set up if you’re already using a Kindle.

4. Listening to Podcasts with the author After a book, I often find myself with a slew of questions I wish I could ask the author. That’s exactly why they get invited to various Podcasts (if they’re alive). With Podcast search engines it’s easy to find a Podcast with the author. The show notes will often reveal what types of questions the interviewer is going after.

What would I like to improve about processing?

As mentioned, I may need a new home for these nuggets instead of index cards. It’s tough to sort them properly, so currently it’s a simple queue based on last review date. I am about a year behind (i.e. I review cards now I wrote about a year ago), so typically I produce cards faster than I can process them. For the time being, I’m OK with it. I destroy a lot of cards when I review that are not relevant to me, or I think are covered by something else. I’ve scurried through them quite a few times to try to find something I was sure I had on a card—this is a frustrating experience. I just don’t have the perfect software for it yet, and I worry a lot about putting this somewhere and having to convert it around. To some extent, this has become my most prized possession in that it’s impossible for me to replace.

Going forward, I’ll likely digitize them to make them searchable. A year or two

from now, I’m going to go through them and review the R and U scores and

correlations with other symbols to find out what works, and what doesn’t. Based

on this, I will create a sorting algorithm for the digitized index cards. Again,

the software in this space is lacking, so it may be a fancy use of Airtable if

nothing better exists by that time.

What are changes I’ve made to processing?

This is the step I’ve invested the most in in the past few years because I feel this is where the most impact is had. In general, I think that people should spend 50-60% of their time in this stage over all others. Most spend the majority of their time in reading. I’ve come to many great realizations writing about cards and applying them to my life and current situations. My past self can recognize an idea as useful, and recognize that there’s no immediate application of it, transcribe it to a card and hope it pops up at a better time. This setup poises me to increase the probability I get the right idea, at the right time. The right time being when it’s most likely to be applied.

Overall, I have not made many changes here other than gradually adding to this system. I hope in a few years to go through the data on the cards and the ratings, to figure out which methods work best for retention. Writing? Flash cards? Memory palaces? Talking to a friend?

Future

I will continue to iterate on this, likely, for the rest of my life. I think everyone deserves a good reading system. It takes years to build one, you can’t start out with this, or any other system—you need to gradually build it over time. The reading habit is most important, then you start paying more attention to what you read, you start highlighting, you start taking notes, you start writing summaries, and slowly a complex system that works for you will evolve and evolve. I hope this can inspire you to invest more in your reading process.

For book recommendations, see my Goodreads profile

especially my reread shelf.