Peak Complexity

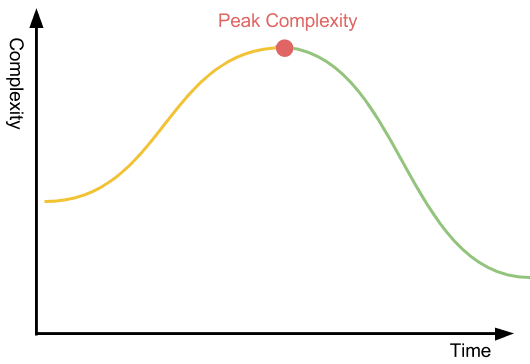

With the teams I work with, we operate with the idea of peak complexity: the time at which a project reaches its highest complexity. Peak complexity has proved a useful mental model to us for reasoning about complexity. It helps inform decisions about when to step back and refactor, how many people should be working on the project at a given point in time, and how we should structure the project.

What we find is that to make something simpler, we typically have to raise the complexity momentarily. If you want to organize a messy closet, you take out everything and arrange it on the floor. When all your winter coats, toques, and spare umbrellas are laid out beneath you, you’re at peak complexity. The state of your house is worse than it was before you started. We accept this step as necessary to organize. Only when it’s all laid out can you decide what goes back in, and what doesn’t to ultimately lower the complexity from the initial point.

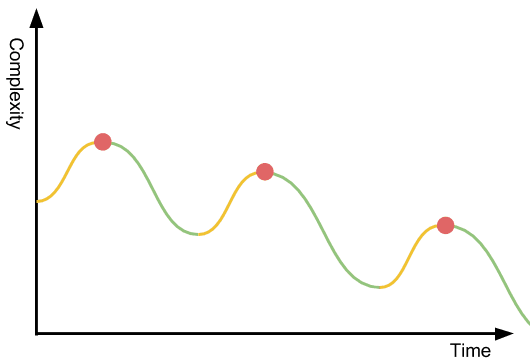

When you’re cleaning your house, you do this one messy place at a time: the bedroom closet, then the attic, and lastly, the dreaded basement. Doing it all at once would be utter mayhem; costumes, stamp collections, coats, and lego sets everywhere. We’re managing our series of peak complexity points to one messy floor-patch at a time.

This model works for software, too. As we embark on a complex project, we need to consider the pending complexity peaks(s). It’s completely okay to add complexity along the journey, sometimes you need to momentarily trade technical debt for speed. But it’s also part of the job to manage your complexity budget. Be honest with your team about where you reside on the curve. The more complexity you add, the harder it is to onboard new members to the team. Typically, your bus factor increases, because few people can hold this complexity in their head at a time. With high complexity, the probability of error increases non-linearly. It’s prudent to review your project’s inflection points and structure it to have many small peaks. This avoids creating a Complexity Everest. A big mountain is tough to climb. It gets exponentially harder the closer you get to the top as oxygen levels decrease, wind increases, temperature drops, and willpower depletes. That’s why you want to structure your project into hills that deliver value every step of the way: day-time hikes with picnic baskets. Sometimes, the inevitable mountain appears—and that’s okay, but be realistic about what it means to the project.

The worst thing you can do is build a complexity mountain and not harvest the simplicity gains on the other side. The descent may require a smaller team and take less time than it took to climb, but is incredibly important work. As I’ve written about before, the more you can simplify the mental model of the software, the more leverage you build. If you fail to recognize peak complexity and descend you may strand there. This is how you end up supporting your project forever. It’s also worth noting that for a project, there’s not just peak complexity, there are other resources you can trade for speed in the short-term:

- Peak Toil. You trade manual operations/lack of automation for getting the first iteration of the project shipped sooner. Just as with peak complexity, it’ll catch up to you.

- Peak Money/Cost. Money is another resource you can often trade for speed, e.g. by leaving optimization to after the initial version has shipped.

- Peak People. This is the point in time where your project has the most staff assigned to it, as the project moves into later phases of its life-cycle it’ll most likely have less people assigned to it. Other projects require more people as the initial version is out. On some projects, again, you can trade people for speed. An opportunity cost comes with that, of course.

- Peak Stress/Work. People can sprint to reach some short-term target, but if you don’t allow them to rest, your people will lose trust in you, get tired, and will shorten their timescale for decisions.

- Peak Sluggishness. For many projects, you can solve performance later to get the first iteration out quicker, too. It may be that it’s not worth solving some algorithmic or data storage problem until you’ve proved that it’s something customers want.

As a lead or project manager, I think it’s your responsibility to be aware of these peaks when trading the amplitude of a peak for speed on the project. If you push the peak too high on too many, your project will go through a tough problem and fail for reasons unrelated to the project.

You might also like...