Shitty First Software Drafts

Writing is known for its ‘shitty first drafts.’ The initial incoherent braindump is part of the process of writing. As the quote goes: “It is by intuition we discover, and by logic we prove.” Intuition is what sparks into the first draft, and logic is what transforms it into clear thinking that concisely communicates an idea.

Painters, writers, and composers are all notorious for throwing away pieces of work that don’t “have it.” They will start over repeatedly to attempt to capture the essence of what they’re trying to share.

These creative fields are blessed and cursed with a vague sense of completeness. You can’t prove that a piece of art communicates the emotion the artist intended. However, software is blessed and cursed by the lack of ambiguity. A test can show that your program does what it’s supposed to do. But that doesn’t mean you can stop. While you may have figured out how to make the machine do what you want, it takes more effort to express your intents to humans clearly. It is tempting to stop when it works, but it is only the beginning. That’s the shitty first draft you’d never turn in. Now you must go through the process to make it as simple as possible for others to understand.

If you don’t make the foundational pieces as simple as possible, the complexity will compound rapidly for the lifetime of the code. The more foundational, the worse the effects. You damage people’s mental models with undigested ideas, poor abstractions, and noise. After the creation, it’s difficult for someone to go back and rethink the piece for simplicity—cleaning up your mess. You will have to explain this complexity for as long as it is around. Instead, build empathy and minimize the interpretive labor as much as you can.

In the book “Bird by Bird,” the author explains her process for writing fiction. Her process is to invent the characters and write short stories about them only to throw them away. Through these stories, she gets to know the characters, one by one. When she feels she knows them well enough, the story will start to unfold. For software, the process should be similar. As you write your patch, you get to know the classes involved, the relationships between them, and the alternative solutions. The better you know them, the simpler you can make the final solution.

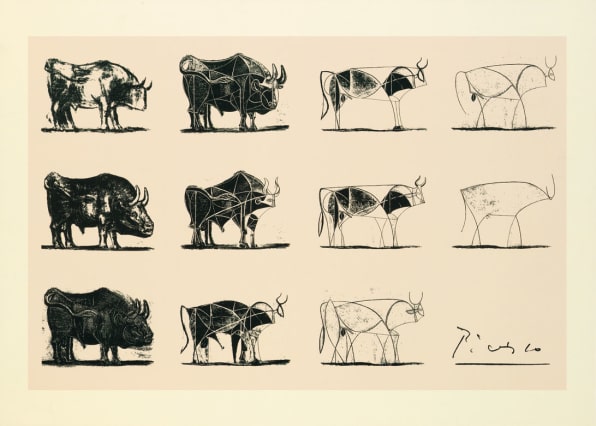

My favorite example of this process comes from Picasso. He had these famous experiments where he’d try to get to the very essence of animals. Could he draw them with a single line in such a way that they would be recognizable to anyone? If you look at the final result, you may think Picasso was a lazy painter who couldn’t draw a full bull. But, you don’t sit down and draw a bull with a single line in your first shot. I challenge you to. You have to get to know the bull and its characteristics. You start by drawing a full bull, and then slowly you take the fluff away until there’s nothing left to take away.

This is how we should design software. Realize that when the test pass, you’ve only managed to draw the first bull. Only a few people go through the ten subsequent iterations to make it as simple as possible.

My high school literature teacher called this process “the acid test.” He said you have to imagine putting your essay into acid, and stringing it back together from the few words that remain. Then do it again. And again.

Good developers don’t confuse a working solution with a final solution. They go through the same painful process as artists, constantly trying to make it simpler to reduce the interpretive labor for others. They understand that if a change is met with “I can’t believe this was so easy!” despite it taking a week—they’ve done their job well. They are allergic to complexity, and continually challenge themselves to simplify. They understand the long-term compounding consequences of a poor abstraction. They understand that simplicity is the prerequisite for reliability.

Tobi, the CEO of Shopify, has mentioned on more than one occasion that git reset --hard (blowing away all your work) is his favorite feature of Git. He’s

said that if you can’t blow away all your work and write it again from scratch

in an hour, you haven’t found the simplest solution yet.

For further reading on this topic, I recommend “A Pattern Language”.