Revision History

Napkin friends, from near and far, it’s time for another napkin problem!

As always, consult sirupsen/napkin-math to solve today’s problem, which has all the resources you need. Keep in mind that with napkin problems you always have to make your own assumptions about the shape of the problem.

I debated putting out a special edition of the newsletter with COVID-related napkin math problems. However, I ultimately decided to resist, as it’s exceedingly likely to encourage misinformation. Instead, I am attaching a brief reflection on napkin math in this context.

In the case of COVID, napkin math can be useful to develop intuition. It became painfully clear that there are two types of people: those that appreciate exponentials, and those that don’t. Napkin math and simple simulations have proved apt at educating about exponential growth and the properties of spread. If you don’t stare at exponential growth routinely, it’s counter-intuitive why you’d want to shut down at a few hundred cases (or less).

However, napkin math is insufficient for informing policy. Napkin math is for informing direction. It’s for rapidly uncovering the fog of war to light up promising paths. Raising alarm bells to dig deeper. It’s the experimenter’s tool.

It’s an inadequate tool when even getting an order of magnitude assumption right is difficult. Napkin math for epidemiology is filled with exponentials, which make it mindbogglingly sensitive to minuscule changes in input. The ones we’ve dealt with here haven’t included exponential growth. I’ve been tracking napkin articles on COVID out there from hobbyist, and some of it is outright dangerous. As they say, more lies have been written in Excel than Word.

On that note, on to today’s problem!

Problem 7

Revision history is wonderful. We use it every day in tools like Git and Google Docs. While we might not use it directly all the time, the fact that it’s there makes us feel confident in making large changes. It’s also the backbone for features like real-time collaboration, synchronization, and offline-support.

Many of us develop with databases like MySQL that don’t easily support revision history. They lack the capability to easily answer queries such as: “give me this record the way it looked before this record”, “give me this record at this time and date”, or “tell me what has changed since these revisions.”

It doesn’t strike me as terribly unlikely that years from now, as computing costs continue to fall, that revision history will be a default feature. Not a feature reserved from specialized databases like Noms (if you’re curious about the subject, and an efficient data-structure to answer queries like the above, read about Prolly Trees). But today, those features are not particularly common. Most companies do it differently.

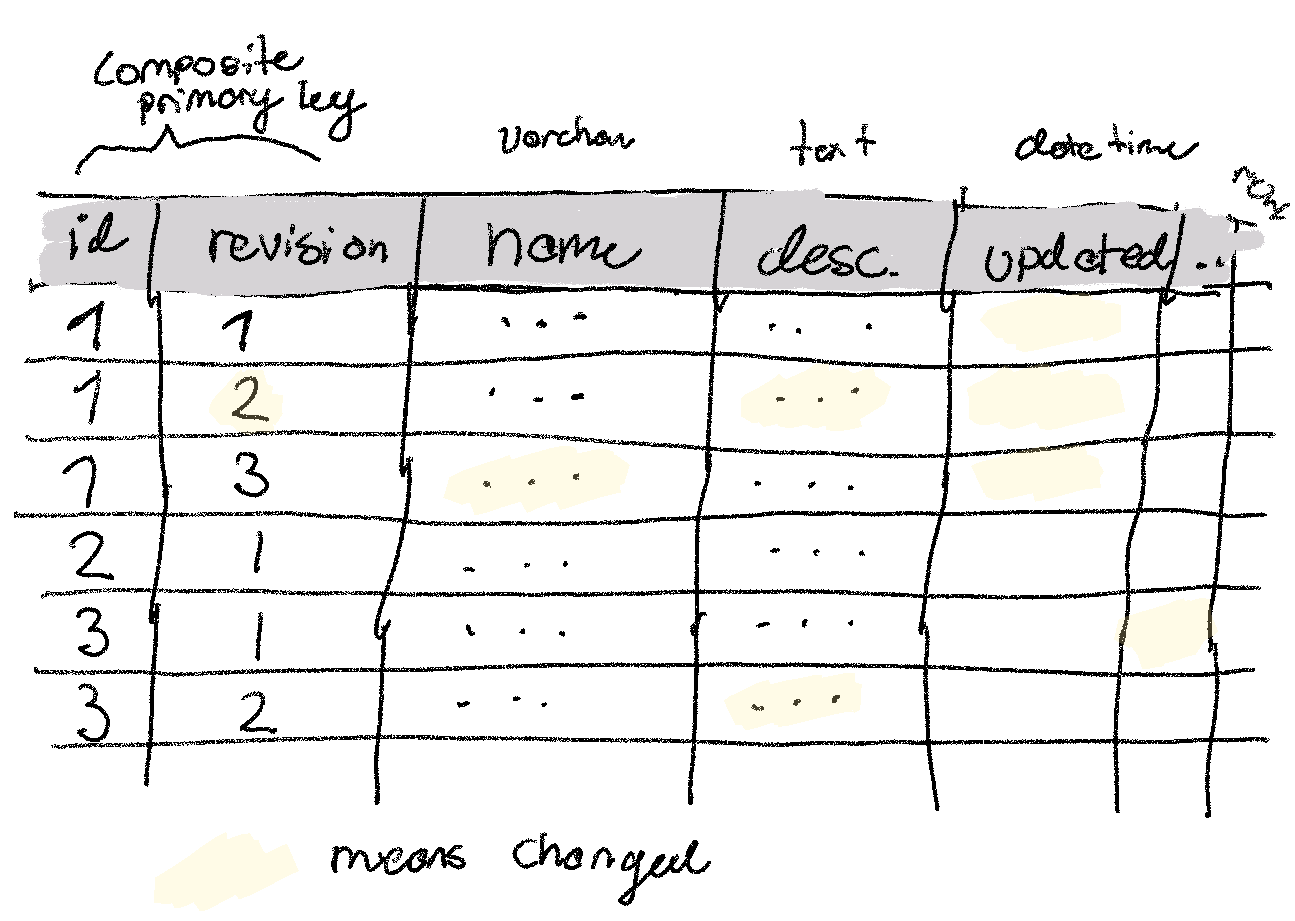

Let’s try to analyze what it would look like to get revision history on top of a standard SQL database. As we always do, we’ll start by analyzing the simplest solution. Instead of mutating our records in place, our changes will always copy the entire row, increment a version_number on the record (which is part of the primary key), as well as an updated_at column. Let’s call the table we’re operating on products. I’ll put down one assumption: we’re seeing about 10 updates per second. Then I’ll leave you to form the rest of the assumptions (most of napkin math is about forming assumptions).

(a) How much extra storage space do you anticipate this simple scheme would require after a month? A year? What would this cost on a standard cloud provider?

(b) Based on (a), would you keep storing it in a relational database, or would you store it somewhere else? Where? Could you store it differently more efficiently without changing the storage engine?

Answer is available in the next edition.

Answer to Problem 6

The last problem can be summarized as: Is it feasible to build a client-side search feature for a personal website, storing all articles in memory? Could the New York Times do the same thing?

On my website, I have perhaps 100 pieces of public content (these newsletters, blog posts, book reviews). Let’s say that they’re on average 1000 words of searchable content, with each word being an average of 5 characters/bytes (fairly standard for English, e.g. this email is ~5.1). We get a total of: 5 * 10^0 * 10^3 * 10^2 = 5 * 10^5 bytes = 100 kb = 0.1 mb. It’s not crazy to have clients download 0.1mb of cached content, especially considering that gzip a blog post seems to compress about 1:3.

The second consideration would be: can we search it fast enough? If we do a simple search match, this is essentially about scanning memory. We should be able to read 100kb in less than a millisecond.

For the New York Times, we might ballpark that they publish 30 pieces of ~1,000 word content a day. While it’d be sweet to index since their beginnings in 1851, we’ll just consider 10 years at this publishing speed as a ballpark. 5 * 10^0 * 10^3 * 30 * 365 * 10 ~= 500mb. That’s too much to do in the browser, so in that case we’d suggest a server-side search. Especially if we want to go back more than 10 years (by the way, past news coverage is fascinating — highly recommend currently reading articles about SARS-COV-1 from 2002). Searching that much content would take about 50ms naively, which might be ok, but since this is only 10 years of even more data, we’d likely want to also investigate more sophisticated data-structures for search.