Positive Unknown-Unknowns

When we make decisions, it’s useful to be cognizant of unknown-unknowns. Almost in every case, we think about unknown-unknowns in a negative sense. If we’re venturing into unknown territory, we accept that it’s likely we’ll stumble upon Black Swans: improbable events that throw a wrench into our plans. Typically, we’ll draw on our experience to take the path we figure has the fewest negative unknown-unknowns. We may choose to stretch something we already know instead of adopting something new. Brooding on negative unknown-unknowns is extremely useful, and fairly commonplace.

I think it’s equally useful to invert the traditional thinking about unknown-unknowns and ask ourselves: How many positive unknown-unknowns might we face with this option? Might we face more positive black swans, than negative? In effect, what would give us the most positive optionality?

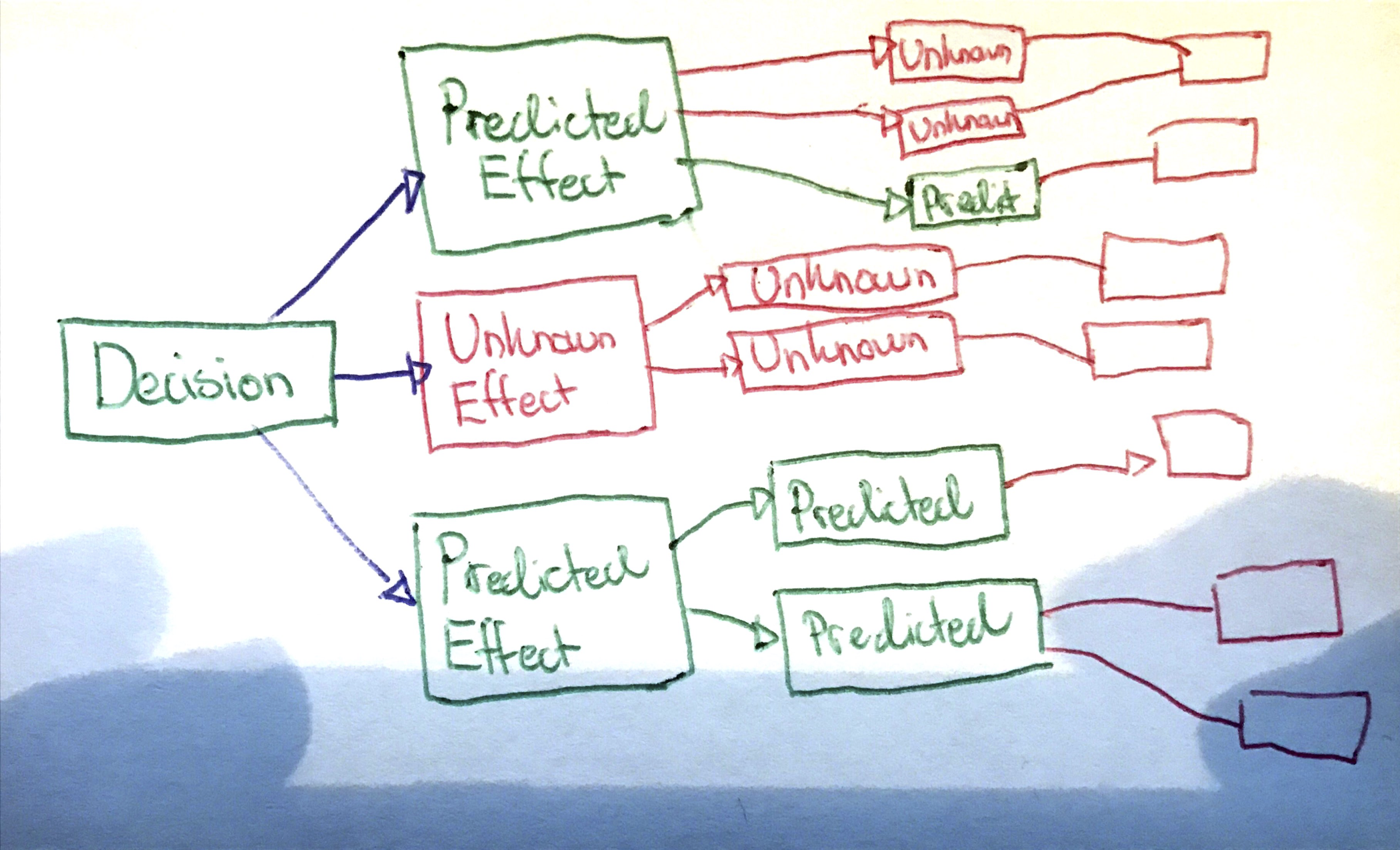

When making decisions, we weigh most strongly the first-order effects. We’re not taught to systematically think through the second- and third-order effects. As we get further away from first-order effects, our ability to predict effects decreases exponentially. There’s a higher chance that we’ve missed second-order effects, than first-order effects. These missed effects are what we call unknown-unknowns. There are too many variables to keep track of and the interactions between them, while governed by simple rules, become unmanageable to the human brain. You can attempt to combat this with expertise, but you must face that you won’t catch them all.

An example might help. Consider the Internet, which had a fairly niche purpose at first. Yet, it seemed to many that connecting the planet would be a good idea. There’s no way that those connecting the globe could’ve anticipated the amount of positive unknown-unknowns ramifications of the Internet. What they did project, however, was that the space of unknown-unknowns positives for the Internet was enormous.

Similarly, if we look at cryptocurrencies today, people are smitten with the potential for the positive unknown-unknowns (and others by greed). What the Internet, cryptocurrencies, and the printing press have in common is that they’re foundational platforms with an enormous surface area for positive unknown-unknowns.

I’ve seen positive unknown-unknowns numerous times when people build platforms. Someone builds something great and simultaneously takes the time to solve the problem one layer deeper than they otherwise might have. They sense the potential in increasing the probability of positive unknown-unknowns, by supplying the vision of a platform. Internally, two years ago we had an employees-only single podcast. Today, we have around ten ranging from training, interviews to learn more about how to build an internal product or history lessons about the company from our executives. When it was clear that there was an internal podcast platform, it exploded. The first podcast went one level deeper to provide a platform, increasing the surface area for positive unknown-unknowns.

We will have to remain humble to the fact that often we can’t predict all effects, positive and negative. We can attempt to reason about their size, but we won’t know for sure. There’s an old Taoist fable that we can interpret as a story unknown-unknown second and third-order effects:

“When an old farmer’s stallion wins a prize at a country show, his neighbour calls round to congratulate him, but the old farmer says, “Who knows what is good and what is bad?”

The next day some thieves come and steal his valuable animal. His neighbour comes to commiserate with him, but the old man replies, “Who knows what is good and what is bad?”

A few days later the spirited stallion escapes from the thieves and joins a herd of wild mares, leading them back to the farm. The neighbour calls to share the farmer’s joy, but the farmer says, “Who knows what is good and what is bad?”

The following day, while trying to break in one of the mares, the farmer’s son is thrown and fractures his leg. The neighbour calls to share the farmer’s sorrow, but the old man’s attitude remains the same as before.

The following week the army passes by, forcibly conscripting soldiers for the war, but they do not take the farmer’s son because he cannot walk. The neighbour thinks to himself, “Who knows what is good and what is bad?” and realises that the old farmer must be a Taoist sage. ”

It is tempting to believe at any of the critical points in this story that you know what will happen next with certainty. With the most prized stallion in the land, riches await! Or, when stolen, that you’ll never see it again. While the series of events in this story seem highly unlikely, it teaches us that effects will happen that we could never have imagined. The sum of the probabilities of unknown-unknowns may outweigh the knowns.

You may be looking at two options for a decision that seem equally good. Have you considered which one has larger optionality long-term? Third-order effects that you could by no means predict? With a small modification, could you increase the surface area for unknown-unknown positives? Can you expose even a fraction of a platform?

Considering positive unknown-unknowns has changed my mind quite a few times in the past year. Contemplating optionality is not about making decisions based on hope. It is one of many mental models in your arsenal to improve your decisions. Each model gives you a new vantage point to see the problem from to help you come to a better decision.