Circuit Breakers

You may have heard of a “circuit breaker” in the context of building resilient systems: the art of building reliable systems from unreliable components. But what is a circuit breaker?

Let’s set the scene for today’s napkin math post by setting up a scenario. Scenario’s pretty close to reality of what our code looked like conceptually when we started working on resiliency at Shopify back in 2014.

Imagine a function like this (pseudo-Javascript-C-ish is a good common denominator) that’s part of rendering your commerce storefront:

function cart_and_session() {

session = query_session_store_for_session();

if (session) {

user = query_db_for_user(session['id']);

}

cart = query_carts_store_for_cart();

if (cart) {

products = query_db_for_products(cart.line_items);

}

}

This calls three different external data-stores: (1) Session store, (2) Cart store, (3) Database.

Let’s now imagine that the session store is unresponsive. Not down, unresponsive: meaning every single query to it times out. Default timeouts are usually hilariously high, so let’s assume a 5 second timeout.

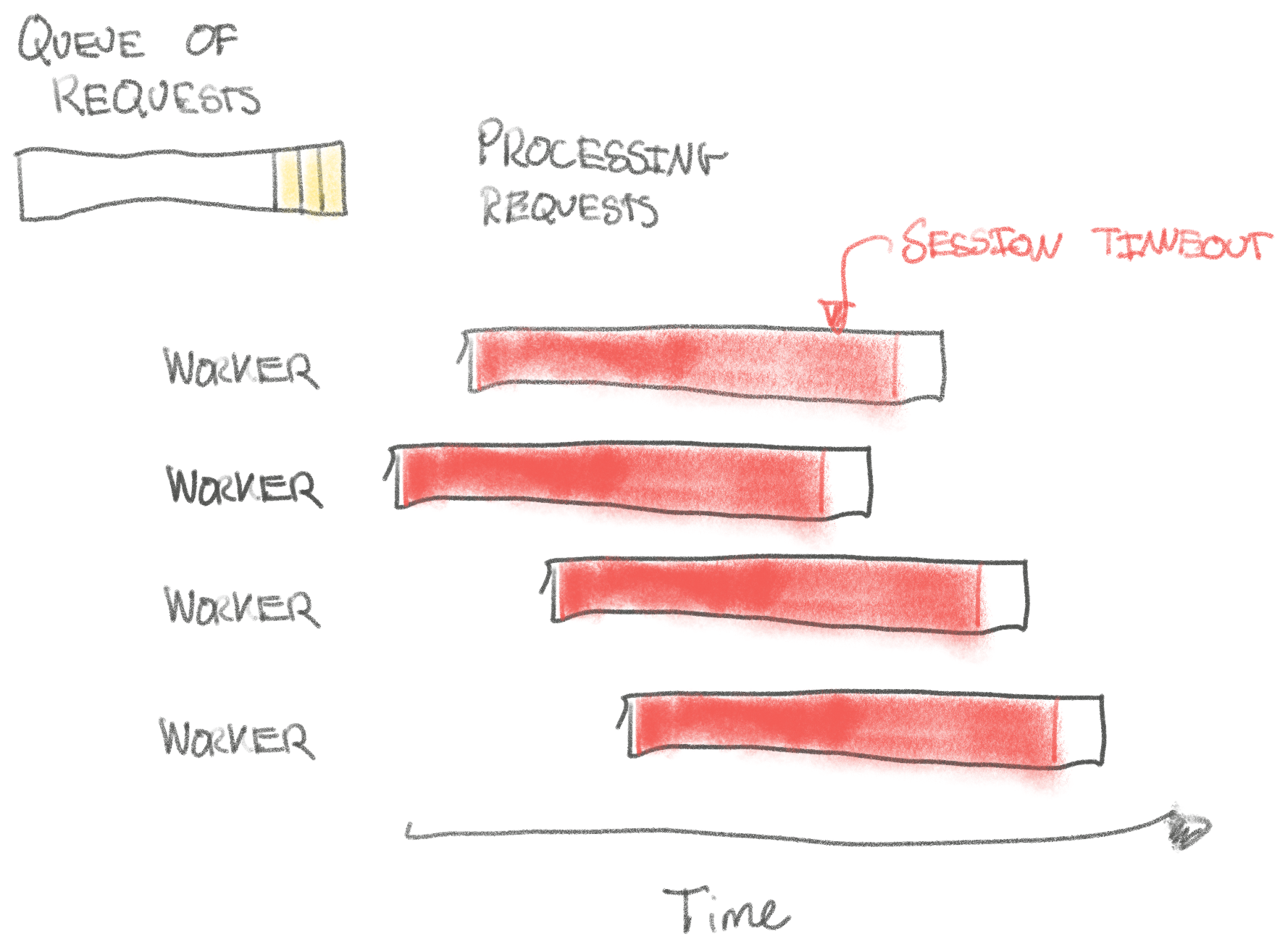

Let’s say we’ve got 4 workers all serving requests with the above code. Under current circumstances with the session store timing out, this means

each worker would be spending 5 seconds in query_session_store_for_session on

every request! This seems bad, because our response time is at least 5

seconds. But it’s way worse than that. We’re almost certainly down.

Why are we down when a single, auxiliary data-store is timing out? Consider that before, requests might have taken 100 ms to serve, but now they take at least 5 seconds. Your workers can only serve 1/50th the amount of requests they could prior to our session store outage! Unless you’re 50x over-provisioned (not a great idea), your workers are all busy waiting for the 5s timeout. The queue behind the workers slowly filling up…

What can we do about this? We could reduce the timeout, which would be a good idea, but it only changes the shape of the problem, it doesn’t eliminate it. But we can implement a circuit breaker! The idea of the circuit breaker is that if we’ve seen a timeout (or error of any other kind we specify) a few times, then we can simply raise immediately for 15 seconds! When the circuit is raising, this means the circuit breaker is “open” (this vocabulary tripped me up for the first bit, it’s not “closed”). After the 15 seconds, we’ll try to see if the resource is healthy again by letting another request through. If not, we’ll open the circuit again.

Won’t raising from the circuit just render a 500? The assumption is that you’ve made your code resilient, so that if the circuit is open for the session store, then you simply fall back to assume that people aren’t logged in instead of letting an exception trickle up the stack.

We can imagine a simple circuit being implemented like below. It has numerous problems, but it should paint the basic picture of a circuit.

circuits = {}

function circuit_breaker(function f) {

// Circuit's closed, everything's likely normal!

if (circuits[f.id].closed) {

try {

f();

} catch(err) {

// Uh-oh, an error occured. Let's check if it's one we should possibly

// open the circuit on (like a timeout)

if (circuit_breaker_error(err)) {

errors = circuits[f.id].errors += 1;

// 3 errors have happened, let's open the circuit!

if (errors > 3) {

circuits[f.id].state = "open";

}

}

}

}

if (circuits[f.id].open) {

// If 15 seconds have passed, let's try to close the circuit to let requests

// through again!

if (Time.now - circuits[f.id].opened_at > 15) {

circuits[f.id].state = "closed";

return circuit_breaker(f);

}

return false;

}

}

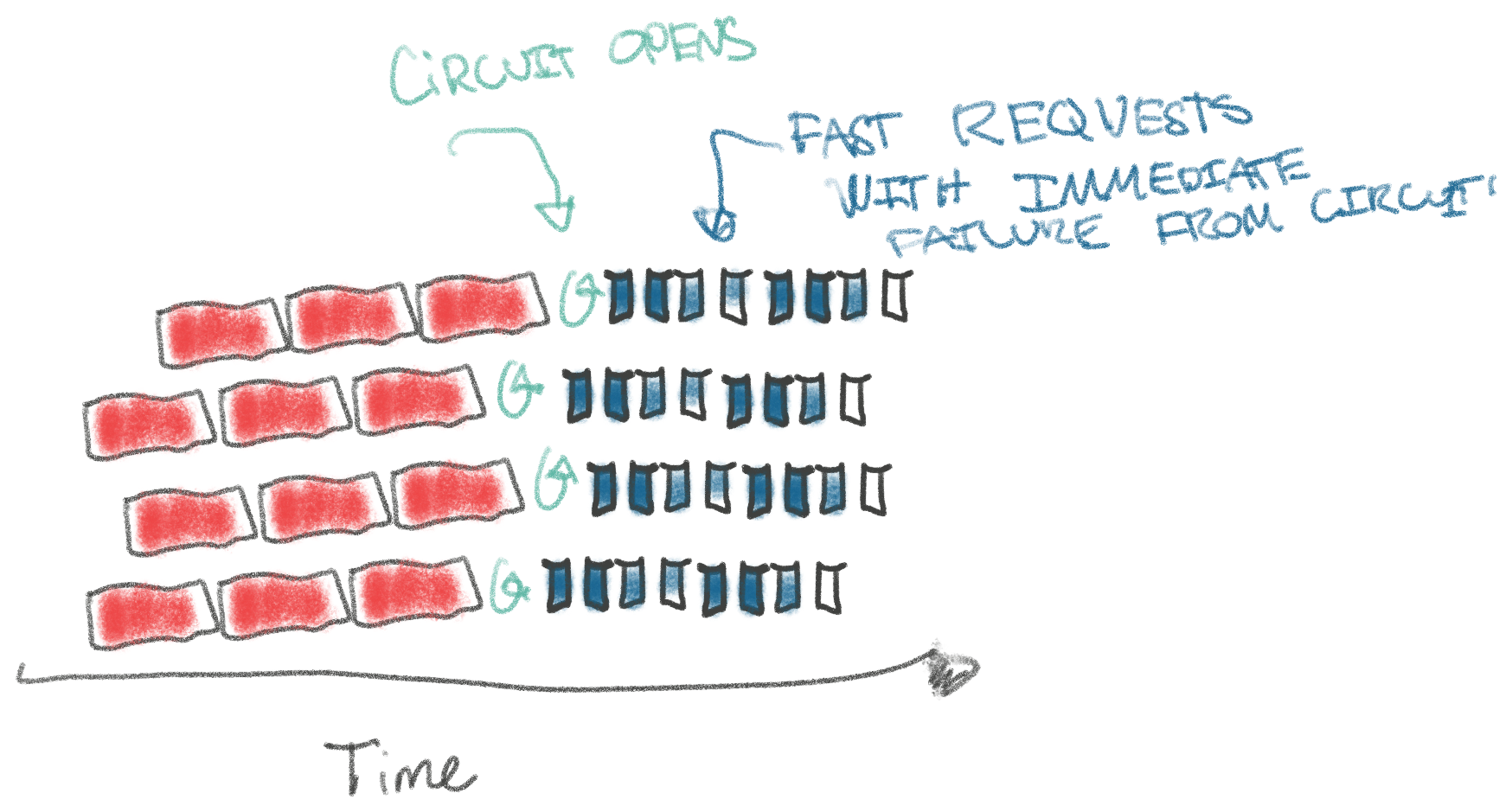

What position does that put us in for our session scenario? Once again, it’s best illustrated with a drawing. Note, I’ve compressed the timeout requests a bit here (this is not for scale) to fit some ‘normal’ (blue) requests after the circuits open:

After the circuits have all opened, we’re golden! Back to normal despite the

slow resource! The trouble comes when our 15 seconds of open circuit have

passed, then we’re back to needing 3 failures to open the circuits again and

bring us back to capacity. That’s 3 * 5s = 15s where we can only serve 3

requests, rather than the normal 15s/100ms = 150!

To do some napkin math, since there’s 15 seconds we’re waiting for timeouts to open the circuits, and 15 seconds with open circuits, we can estimate that we’re at ~50% capacity with this circuit breaker. The drawing also makes this clear. That’s a lot better than before, and likely means we’ll remain up if you’re over-provisioned by 50%.

Now we could start introducing some complexity to the circuit to increase our capacity. What if we only allowed failing once to re-open the circuit? What if we decreased the timeout from 5s to 1s? What if we increased the time the circuit is open from 15 seconds to 45 seconds? What if we open the circuit after 2 failures rather than 3?

Answering those questions is overwhelming. How on earth will we figure out how to configure the circuit so we’re not down when resources are slow? It might have been somewhat simple to realize it was ~50% capacity with the numbers I’d chosen, but add more configuration options and we’re in deep trouble.

This brings me to what I think is the most important part of this post: Your circuit breaker is almost certainly configured wrong. When we started introducing circuit breakers (and bulkheads, another resiliency concept) to production at Shopify in 2014 we severely underestimated how difficult they are to configure. It’s puzzling to me how little there’s written about this. Most assume that you drop the circuit in, choose some decent defaults, and off you go. But in my experience in your very next outage you’ll find out it wasn’t good enough… that’s a less than ideal feedback loop.

The circuit breaker implementation I’m most familiar with is the one implemented in the Ruby resiliency library Semian. To my knowledge, it’s one of the more complete implementations out there, but all the options makes it a devil to configure. Semian is the implementation we use in all applications at Shopify.

There are at least five configuration parameters relevant for circuit breakers:

error_threshold. The amount of errors to encounter for the worker before opening the circuit, that is, to start rejecting requests instantly. In our example, it’s been hard-coded to 3.error_timeout. The amount of time in seconds until trying to query the resource again. That’s the time the circuit is open. 15 seconds in our example.success_threshold. The amount of successes on the circuit until closing it again, that is to start accepting all requests to the circuit. In our example above, this is just hard-coded to 1. This requires a bit more logic to have a number > 1, which better implementations like Semian will take care of.resource_timeout. The timeout to the resource/data-store protected by the circuit breaker. 5 seconds in our example.half_open_resource_timeout. Timeout for the resource in seconds when the circuit is checking whether the resource might be back to normal, after theerror_timeout. This state is calledhalf_open. Most circuit breaker implementations (including our simple one above) assume that this is the same as the ‘normal’ timeout for the resource. The bet Semian makes is that during steady-state we can tolerate a higher resource timeout, but during failure, we want it to be lower.

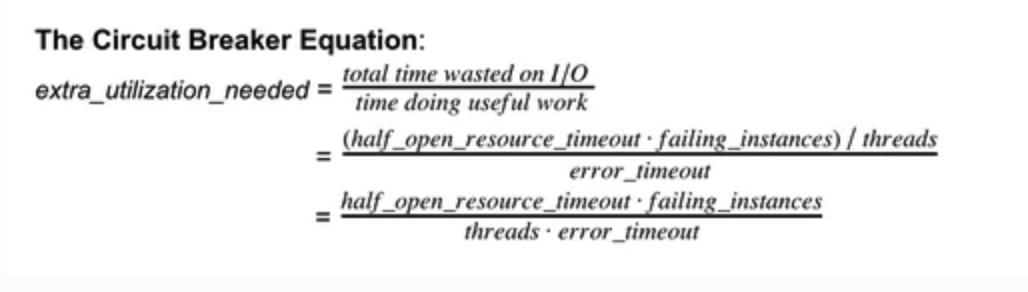

In collaboration with my co-worker Damian Polan, we’ve come up with some napkin math for what we think is a good way to think about tuning it. You can read more in this post on the Shopify blog. This blog post includes the ‘circuit breaker equation’, which will help you figure out the right configuration for your circuit. If you’ve never thought about something along these lines and aren’t heavily over-provisioned, I can almost guarantee you that your circuit breaker is configured wrong. Instead of re-hashing the post, I’d rather send you to read it and leave you with this equation as a teaser. If you’ve ever put a circuit breaker in production, you need to read that post immediately, otherwise you haven’t actually put a working circuit breaker in production.

Hope you enjoyed this post on resiliency napkin math. Until next time!