Adjacent Possible: Model for Peeking into the Future

There are 100s of cases of important discoveries being made independently by different people at almost exactly the same time: calculus (1600s), the telegraph (1837), the light bulb (1879), the jet engine (1840), and the telephone (1876). A recent example was Spectre/Meltdown (2018), possibly the most impactful publicly disclosed security vulnerability of the past decade. Despite its fiendish complexity it was discovered independently by two teams that year.

Why does this happen?

In “Where Good Ideas Come From,”, Johnson explains the idea of the ‘adjacent possible’, pioneered by Stuart Kauffman about how biological systems morph into complex systems. The adjacent possible idea explains simultaneous innovation. It’s one of those ideas that to me was so powerful it’s hard to remember how I thought about innovation prior to learning about it.

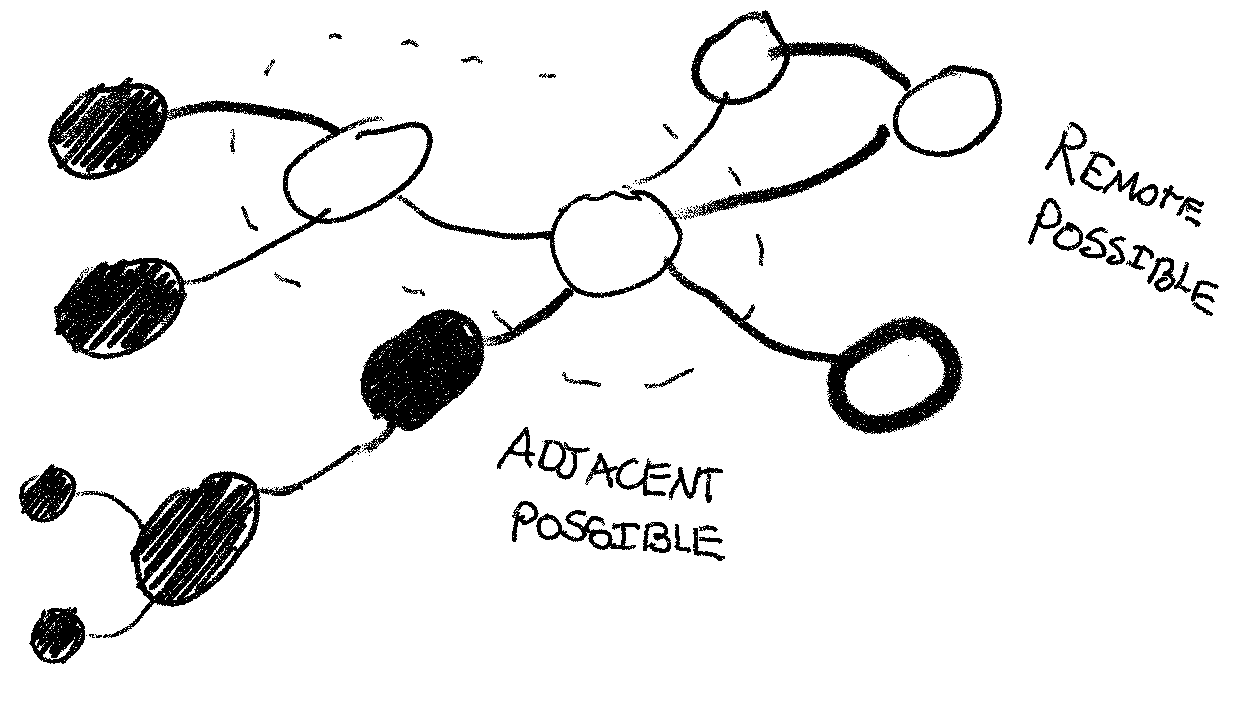

To borrow Johnson’s analogy for the adjacent possible: when you build or improve something, imagine yourself as opening a new door. You’ve unlocked a new room. This room, in turn, has even more doors to be unlocked. Each innovation or improvement unlocks even more improvements and innovations. What the doors lead you to is what we call the ‘adjacent possible.’ The adjacent possible is what’s about a door away from being invented. I like to visualize the adjacent possible as coloured (“built”) and uncoloured (“not built”) nodes in a simple graph:

In human culture, we like to think of breakthrough ideas as sudden accelerations on the timeline, where a genius jumps ahead fifty years and invents something that normal minds, trapped in the present moment, couldn’t possibly have come up with. But the truth is that technological (and scientific) advances rarely break out of the adjacent possible; the history of cultural progress is, almost without exception, a story of one door leading to another door, exploring the palace one room at a time. — Steven Johnson, Where Good Ideas Come From

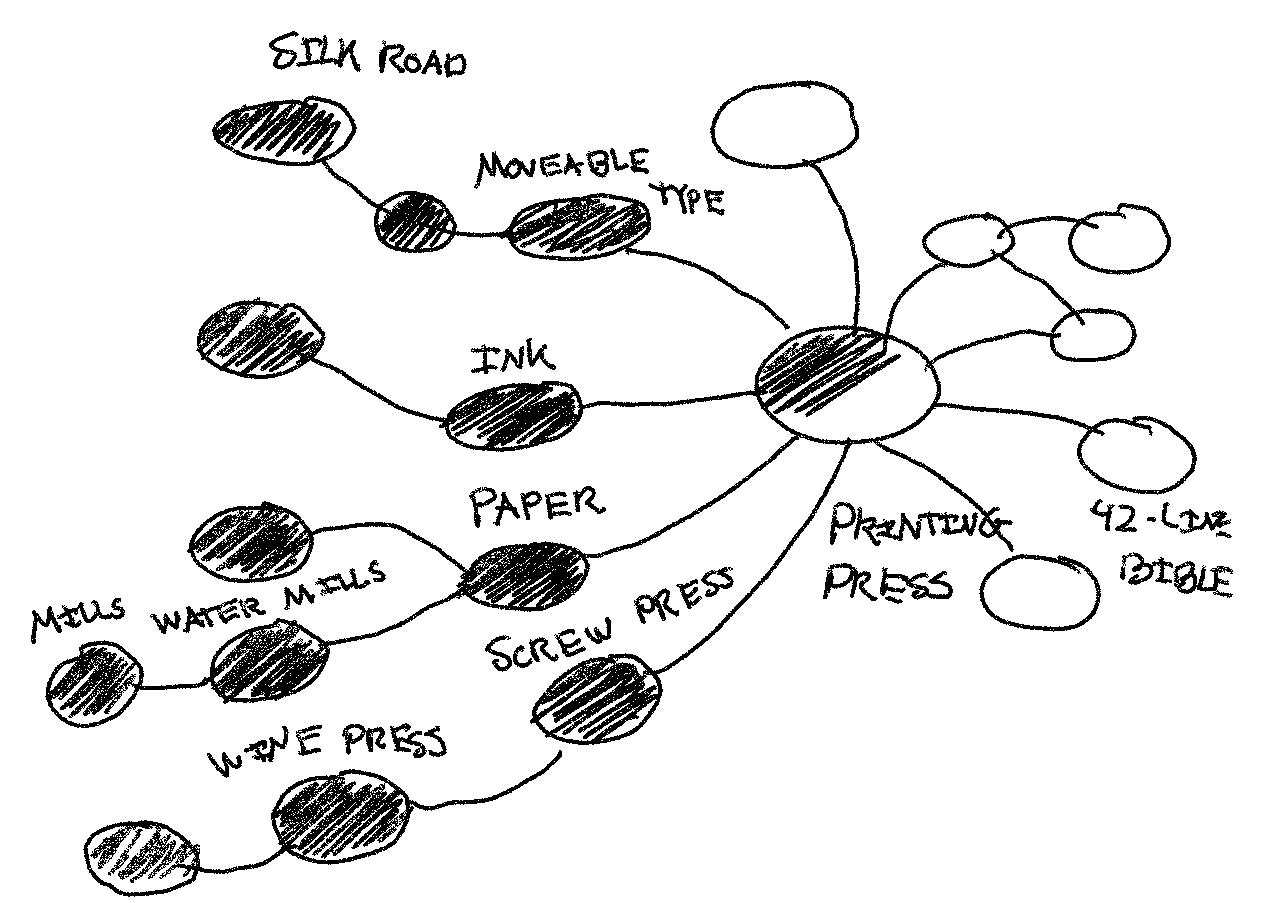

When Gutenberg invented the printing press, it was in the adjacent possible from the invention of movable type, ink, paper, and the wine press. He had to customize the ink, press, and invent molds for the type — but the printing press was very much ripe for plucking in the adjacent possible.

When you internalize it, you start seeing it everywhere.

Here’s Safi Bahcall painting a picture of navigating the adjacent possible, focusing in particular on the importance of fundamental research, a door opener that might not always get the credit and funding it deserves:

“The vast majority of the most important breakthroughs in drug discovery have hopped from one lily pad to another until they cleared their last challenge. Only after the last jump, from the final lily pad, would those ideas win wide acclaim.” — Safi Bahcall, Loonshots

Of course, it took ingenuity for Gutenberg to combine these components to make the printing press. It’s certainly a pattern that the inventor has a profound familiarity with each component. Gutenberg grew up close to the wine districts of South-Western Germany, so he was familiar with the wine press. He had to customize the press, in the same way that much experimentation lead him to come up with an oil-based ink that worked with his movable type (for which he needed to invent molds).

But reality is that if Gutenberg hadn’t invented the printing press, someone else would have. The inventors of the transistor admitted this outright. The Bell Labs semiconductor team understood that when you are picking off the adjacent possible, someone else will get there eventually. In this case, the transistor had come into the adjacent possible from the increased understanding of e.g. the basic research in atomic structure and understanding of electrons conducted by scientists such as Bohr and J. J. Thompson.

“There was little doubt, even by the transistor’s inventors, that if Shockley’s team at Bell Labs had not gotten to the transistor first, someone else in the United States or in Europe would have soon after.” — Jon Gertner, The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation

Edison came to this conclusion too:

I never had an idea in my life. My so-called inventions already existed in the environment – I took them out. I’ve created nothing. Nobody does. There’s no such thing as an idea being brain-born; everything comes from the outside. — Edison

Numerous quotes can be found about how innovations are plucked out of the adjacent possible like ripe fruits:

[Y]ou do not [make a discovery] until a background knowledge is built up to a place where it’s almost impossible not to see the new thing, and it often happens that the new step is done contemporaneously in two different places in the world, independently. — a physicist Nobel laureate interviewed by Harriet Zuckerman, in Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States, 1977

The adjacent possible is a possible explanation for why simultaneous innovation is so common.

You may recognize the adjacent possible as another angle on Newton’s phrase that we ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’ (coloured nodes in the adjacent possible). ‘Great artists steal’, because otherwise how would we launch into the adjacent possible? The greatest artists might just be the ones that create the nodes with the most connections, such as Picasso’s influence in cubism, or Emerson’s in transcendentalism.

You might initially think this is a depressing thought. Are all innovations inevitable? Some teams in history have mowed through the adjacent possible at unprecedented speeds. Think of the Manhatten Project. The Apollo Project. Neither of those were in the adjacent possible. They were in the far remote possible. Many, many doors out. But these teams pushed through. To a company, the momentum provided by breaking through the adjacent possible first can be difficult to catch up with, such as Google and their page-rank search algorithm. Some areas might be simply neglected, e.g. pandemic prevention.

The adjacent possible can teach us an important lesson about being too early. To someone working in the adjacent possible, being too early and wrong is one and the same. I’ve heard Tobi Lutke say a few times that “predicting the future is easy, but timing it is hard.” Sure, we know that autonomous vehicles are coming (predicting the future), but are you wiling to put any money on when (predicting timing)?

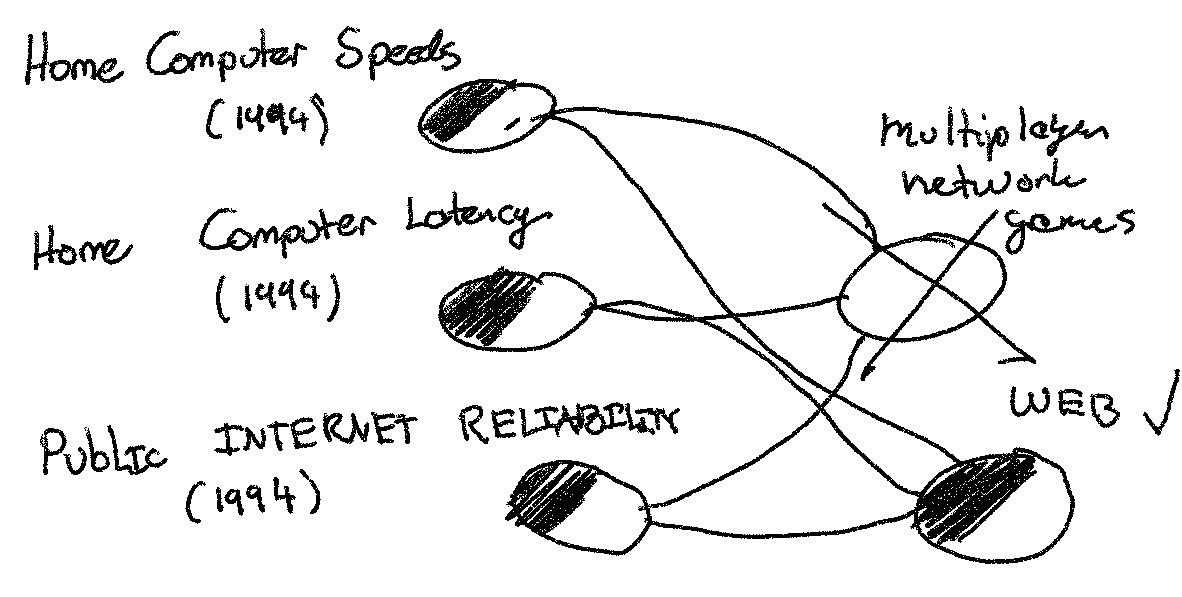

For example, residential internet was not geared yet for responsive online games in the early 90s. It was too early, even if game developers knew it was eventually going to be a thing. It was in the remote possible, but not the adjacent possible. Not enough pre-requisite doors had been opened: home internet speed weren’t good enough, research on how to deal with network latency was poor, and setting up servers all around the world to minimize latency was a lot of work. Being too early means confusing the adjacent and remote possible.

Despite online gaming being too early to become ubiquitous, the stage was set for the web. Half-coloured nodes signal immaturity:

While Wilbur Wright knew we’d one day fly (remote possible), he had no idea if it was in the adjacent possible. He especially didn’t know the timing. But he went to the Kitty Hawk sand dunes with their flimsy plane anyway:

“I confess that, in 1901, I said to my brother Orville that men would not fly for fifty years. Two years later, we ourselves were making flights. This demonstration of my inability as a prophet gave me such a shock that I have ever since distrusted myself and have refrained from all prediction—as my friends of the press, especially, well know. But it is not really necessary to look too far into the future; we see enough already to be certain that it will be magnificent. Only let us hurry and open the roads.” — David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

Bell Labs developed the “picture phone” in the 1960s and 1970s, but they found

themselves branching off nodes in the adjacent possible that made it possible,

but without product/market fit. It’s possible to navigate into the adjacent

possible using the wrong doors: camera + cables + packet_switching + tv does

not necessarily equal a successful commercial ‘video phone’. Video telephony

wouldn’t be in the adjacent possible in a shape consumers would embrace for

another 40-50 years when convenience, price, and form factor would change with

every laptop having a webcam and every phone a front-facing camera. Babbage also

got his timing wrong. He was ~100 years too early with the first computer

design, too.

These are individual failures, but part of a healthy system. We need people to try. While I believe this model is useful to reason about what can be built, it’s just as likely to make you reason incorrectly about why not to build something. You may very likely use this model to be wrong, as an excuse not to be venture into the fog of war. You won’t always know all your dependencies.

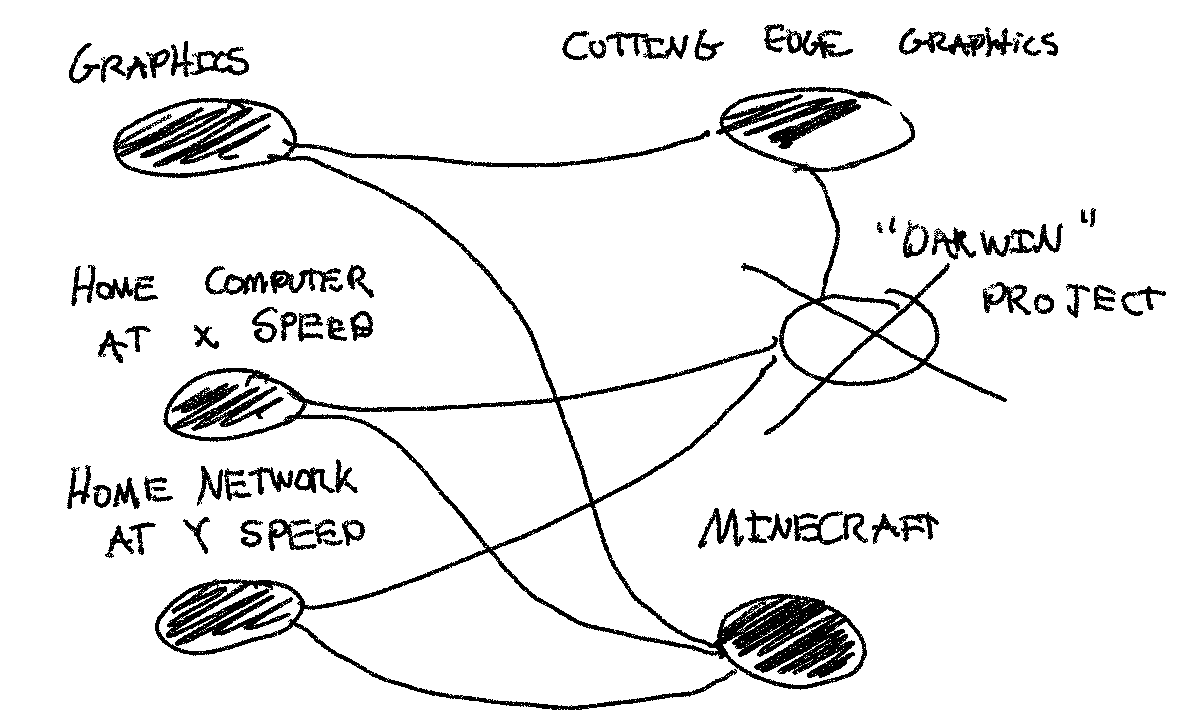

In the late 90s, LEGO was aggressively diversifying from the brick into video games, movies, theme parks, and more. Like the plastic mold had enabled the brick’s transition from wood to plastic, they thought that a digital environment with all possible bricks might start the next wave of innovation for LEGO. They bought the biggest Silicon Graphics machine in all of Scandinavia and put it in a tiny town in Denmark to computer-render the bricks to perfection. LEGO was eager to use the newest graphics technology, the most recently opened door, and marry it with LEGO. Unsurprisingly, the graphics team never shipped anything. When a door’s just been opened, you’re almost certainly going to run into problems with immaturity (a contemporary example would be cryptocurrency). You only have to look at Minecraft’s success a decade later to know what could’ve succeeded: much simpler graphics. LEGO must’ve grinned their teeth when they saw Minecraft take off.

Just because big graphics computers exist doesn’t mean you have to use them. It’s very easy to confuse the eventually/remote possible with the adjacent possible. If you find yourself pushing, pushing, and pushing, but every dependency seems to fail you — your dependencies are too immature. Every project has dependencies, but only the immature ones stand out. You don’t think about electricity as a risky dependency for a project (but you might have in the 1880s), but consumer adoption of VR certainly would be. Smartphones might have been a risky dependency a decade ago, but wouldn’t be considered risky by anyone today. QR-codes might have appeared risky in the West 5-years ago, but is somewhere between “people get it” and “not completely mature” now. In China, however, it’s common that food menus come with QR-codes.

When the transistor was invented at Bell Labs, Bell didn’t immediately replace every vacuum tube amplifier with it in their telephony cabling (amplifiers are used to counteract the natural fading of the signal over long distances). It would take at least a decade to get the price, manufacturing, and reliability of the transistor to the point where it could replace the vacuum tube with half a century of R&D behind it. In fact, they were still laying down massive, cross-country and oceanic cables with vacuum tubes for years after the transistor was invented, patiently waiting it to mature. I’m sure you’ve seen a project fail because, by analogy, you ‘started cabling with transistors immediately after its discovery.’ Sometimes you just need to bite your lip and go with the vacuum tube.

Despite this, it didn’t make Bell any less excited about the transistor. They

knew that the vacuum tube’s potential had been maxed out, while the transistor’s

was just starting. Even today, as we reach 5nm (orders and orders of magnitude

smaller and faster) transitors, the transitor’s potential still hasn’t been

depleted. Although we’re inching closer and closer…

“Gordon Moore suggested what would have happened if the automobile industry had matched the semiconductor business for productivity. “We would cruise comfortably in our cars at 100,000 mph, getting 50,000 miles per gallon of gasoline,” Moore said. “We would find it cheaper to throw away our Rolls-Royce and replace it than to park it downtown for the evening… . We could pass it down through several generations without any requirement for repair.”” — T.R. Reid, The Chip

Wilbur Wright made a similar remark about the limits of airship, after trying one for the first time on a trip to Europe:

[Wilbur] judged it a “very successful trial.” But as he was shortly to write, the cost of such an airship was ten times that of a Flyer, and a Flyer moved at twice the speed. The flying machine was in its infancy while the airship had “reached its limit and must soon become a thing of the past.” Still, the spectacle of the airship over Paris was a grand way to begin a day.” — David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

It’s important to note that improving something existing can open doors just as much as inventing something entirely new. When gas gets 20% cheaper, people don’t just drive 20% more, they might drive 40% more. Behaviour changes. Suddenly it looks economical to move a little further out, visit that relative who lives in the country, or drive 10 hours on vacation.

As another example, the current wave of AI is fuelled by the massive improvements in compute speed over the past few decades, partly from graphics cards originally developed for video games. AI had been hanging out in the remote possible for decades, just waiting for compute to hit a certain speed/cost threshold to make them economically feasible. You might not use AI to sort your search results if it costs $10 in compute per search, but when the cost has generously compounded down to a micro-dollar, it very well might be.

The same iterative improvements are what made the transistor so successful. Fundamentally, it can do the same as a vacuum tube: amplify and switch signals. Initially, it was much more expensive, but smaller and more reliable (no light to attract bugs) — which allowed it to flourish only in niche use-cases far upmarket, e.g. in the US millitary. But over time, the transistor beat the vacuum tube in every way (although, some audiophiles still prefer the ‘sound’ of vacuum tubes?!).

To use our new vocabulary, the transistor only initially expanded the adjacent possible for a few cases. Over time as iterative, consistent improvements were made to price, size, and reliability, the transistor became the root of the largest expanse of the ‘possible’ in human history. It didn’t open doors, it opened up new continents. A more contemporary example might be home and mobile Internet speeds, for which consistent, iterative improvements has expanded the adjacent possible with streaming, video games, video chat, and photo-video heavy social media.

It’s not possible to predict exactly what doors an improvement unlocks. This is a space of unknown-unknowns, but, hopefully positive ones. If we look at history, making things cheaper, smaller, faster, and more reliable tends to expand the adjacent possible. It wasn’t some magical new invention that made AI take off in the past 7-10 years, it was iterative changes: cheaper, faster compute, available on demand in the Cloud. Every time these improve by 10%, something new is feasible.

As an example of perfect timing into the adjacent possible, consider Netflix’ pivot into streaming. The technology they used initially was a little whacky (Silverlight), but it was good enough to give them an initial momentum that’s still carrying them today. They timed the technology and the market perfectly: home Internet speeds, browser technology, etc.

When you find yourself in a spot where you have your eyes on something that’s a few doors out from where you’re standing, that means it’s time to reconsider your approach. When Apple released the iPod in 2001, they surely were eyeing a phone in the remote possible. They knew that going straight for it, they’d be blasting through doors at a pace that’d yield an immature, poor product. They found a way to sustainably open the doors for a phone through the iPod. When you find a seemingly intractable problems, there’s almost always a tractable problem worth solving hiding inside of it as a stepping stone.

Framing problems as the ‘adjacent possible’ has been a liberating idea to me. In the work I do, I try to find the doors that lead to the biggest possible expansion of the possible. That’s what makes platform work so exciting to me.